Expectations are high for the COP28 climate conference, hosted this year by the United Arab Emirates in Dubai. These annual United Nations (UN) conferences bring together nations, corporations, financiers, academics, and activists to evaluate progress on climate and catalyze further action. A significant part of the conversation will cover technical details and developments in climate science, social policy, and financing required for emissions mitigation. But behind the declared purpose, COPs are also an important exercise of national soft power.

Soft power is defined as a nation’s ability to influence the preferences and behaviors of international actors (e.g. states, corporations, communities) by persuasion or attraction, rather than coercion.

Some national actors will exercise their soft power for the declared purpose of mitigating climate change and its effects. For others, however, COP28 is a stage for much wider agendas—cultural, economic, diplomatic, political, and even military.

So as the world’s attention turns towards the UAE, we explore the complex linkages between sustainability and soft power.

Brand Finance has monitored the strength and value of nation brands for 20 years, publishing its Global Soft Power Index (GSPI)—the world’s most comprehensive research study on perceptions of nation brands—since 2020. In the latest iteration, Brand Finance evaluates nation brands on four aspects of environmental sustainability: cities and transport, support for global action on climate change, green energy and technologies, and environmental protection.

Because sustainability issues carry influence that crosses geographic borders, it is a natural extension of soft power. On top of this, a country’s sustainability commitments have clear scope to affect other actors in the international arena, be they states, corporations, communities, or publics. Consequently, nations influence the preferences and behavior of those actors. Understanding perceptions is key for international success, where strong soft power increases ability to attract investment, trade, talent, and tourism, and therefore reputation.

Each year’s COP represents sustainability diplomacy through soft power. Parties aim to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, as defined by the 1987 Brundtland Report. The COP28 agenda is a tall order, with cross-cutting themes of technology and innovation, inclusion, frontline communities, and finance. All attention will be on nations in the planned global stocktake, which assesses each’s progress against existing declared climate commitments. Discussions will also continue about supplying the loss and damage fund formed at COP27 in Sharm al Sheikh, Egypt, set to compensate nations for damage from climate change impacts.

Sustainable Futures and Soft Power Dimensions

A closer look at our data indicates that there is a relationship between sustainability and soft power. The latest GSPI enhances the evaluation of sustainability in its methodology, with a new pillar of Sustainable Futures that captures four aspects of environmental sustainability (Table 1). Prior GSPIs had sustainability-linked attributes, but they were more indirect. Nearly half of attributes that drive national soft power (46%) relate to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) themes.

| Environmental | Socioeconomic | Governance |

| Sustainable cities and transport | A strong and stable economy | Politically stable and well-governed |

| Invests in green energy and technologies | Helpful to other countries in need | High ethical standards and low corruption |

| Acts to protect the environment | Strong educational system | Trustworthy media |

| Supports global efforts to counter climate change | Tolerant and inclusive | Respects rule of law and human rights |

Economic and political stability are understandably core drivers of soft power, reflected in their positions as the first and third most important drivers of national reputation (Table 2). More surprising is the powerful role of ‘pure’ sustainability attributes. Sustainable Cities and Transport is the fifth most powerful driver of soft power, accounting for 4.6% of influence on reputation, while Invests in Green Energy and Technologies is the seventh strongest driver (3.9%).

| 1. A strong and stable economy (8.9%) |

| 2. Internationally admired leaders (6.2%) |

| 3. Politically stable and well-governed (5.9%) |

| 4. Easy to do business in and with (5.1%) |

| 5. Sustainable cities and transport (4.6%) |

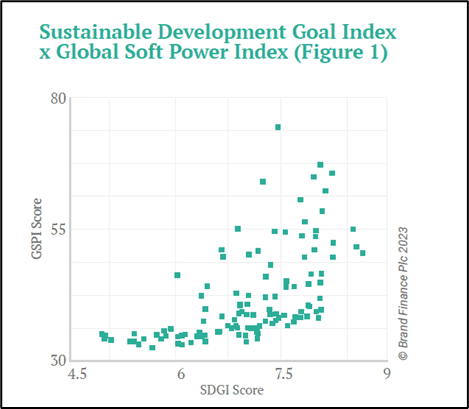

The analysis in Figure 1 plots national Global Soft Power Index (GSPI) scores against each’s score on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Index, an aggregate measure of overall performance against the UN SDGs. The relationship is not a perfect one and there are factors such as population, economic power, cultural influence at play; nevertheless, the correlation coefficient of 0.56 demonstrates a clear relationship between UN SDG performance and soft power.

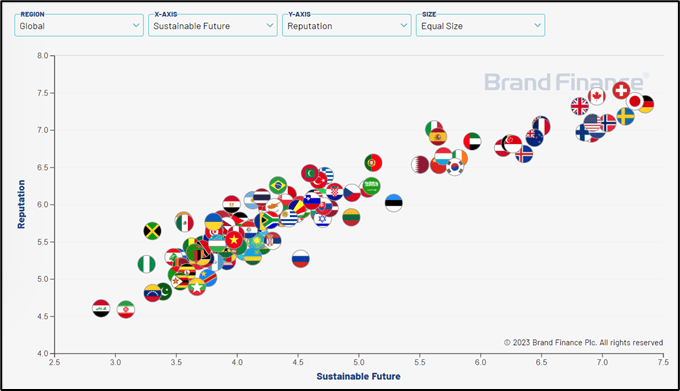

Looking at some outputs from Brand Finance’s soft power dashboard, we can see clear relationships between sustainability and other key components of soft power. For example, in terms of reputation (Figure 2), we see a correlation of r = 0.93.

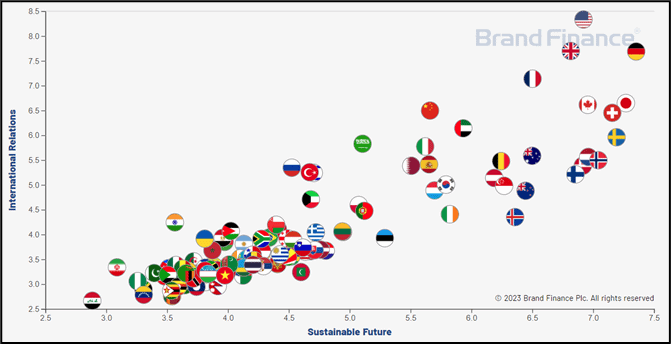

This influence on reputation would appear to have tangible effects on the application of soft power, too. There is a correlation r = 0.88 between sustainability and influence in international relations (Figure 3).

COP28’s tall agenda expectations will further steer the sustainability reputations that nations build, impacting broader national activities. This coincides with k key areas for the application of soft power: Diplomacy, Investment, and Business & Trade.

Diplomacy

Diplomatic settings most clearly place sustainability in a soft power context. Particularly interesting are the dual relationships existing in diplomacy. National governments exercise diplomatic soft power to persuade others to make commitments at major conferences (e.g., COPs). At the same time, these events present an opportunity for nations, particularly the host, to present themselves as key actors at the heart of negotiations and as leaders in sustainability.

At these annual conferences, smaller nations that might be overlooked in other dimensions have built a soft power platform around sustainability. Major climate conferences provide a rare opportunity for all voices to be heard on the world stage. This is particularly important for island states, who stand to be hit first by the worst effects of climate change, and Indigenous peoples, who have long been sustainable custodians of their land and fight displacement and degradation. Recent COPs have garnered criticism for their stakeholder selection, inspiring activism from younger generations and marginalized perspectives to demand a seat at the table.

Moreover, dialogue on the just transition— greening global energy sourcing while monitoring equity concerns—brings differences in responsibility for climate mitigation to light. Global North nations benefit from favorable economic positioning, technological innovation, and adoption. These realities are a product of high emissions and industrialization. Countries in the Global South not yet at this point in their trajectories apply the right to development, recognized by UN Human Rights, to climate change; in other words, does the right to develop imply a right to emit? This interdisciplinary debate asks us to consider if permission to create emissions, an action with negative effects on health and wellbeing via warming, ought to be granted on the grounds that others did so in the past.

Investment

It is widely recognized that significant financial flows need to be generated and maintained to fund this just transition. The parameters for mitigation are defined by a carbon budget, which projects the amount of emissions that will constrain warming to various limits, such as the targets of the Paris Agreement. Despite general scientific consensus on the size of the carbon budget, the financial backing necessary to keep the world within these bounds is not yet mobilized. Stakeholders tasked with funding the transition include public governments, private financial institutions, and multilateral development banks.

The energy transition is one facet of the overall climate adaptation gap observed by the United Nations, whereby the worsening impacts of climate change continue to outpace society’s investment and planning levels. Governments are not on track to meet their declared net zero pledges, with the UN Environment Programme’s 2023 Emissions Gap projecting between 2.5° and 2.9°C of warming by 2100, depending on execution levels and climate finance availability. Alignment with the Paris Agreement entails warming below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C; only in an extreme scenario where all existing net zero pledges from both governments and corporations were met was warming limited to around 2°C.

Further, implementation challenges span from R&D investment through to the market’s eventual pull and adoption. These are effects of the credibility gap from government actors. Despite dedication that nations may convey at events like annual COPs, supporting policies to ensure follow-through are lacking. For example, a nation’s net zero target may be insufficiently backed by legislative action—like subsidies for green technological investment, enhanced oversight of ESG disclosures, and fossil fuel phase-out mandates— rendering it unable to fulfill well-intentioned (and non-binding) pledges.

On the litigative side of negotiations, sustainability is clearly understood to go beyond national boundaries and traverse social, economic, and environmental dimensions. Take last year’s COP27, for example, which established a loss and damage fund to address the global impact of emissions regardless of geographic origin. The fund attributes liability to damages from climate change, which felt most strongly by vulnerable nations. These can be likened to distributing climate reparations. Its funding sources were recently determined ahead of COP28, though magnitudes are yet to be agreed. What remains clear is that nations have differentiated responsibilities for generating emissions reductions based on their contribution to aggregate emissions.

Business & Trade

National reputation-building for sustainability is pronounced during the ongoing green energy shift. Denmark’s strong sustainability reputation is based on its swift adoption and scale of renewable energy industry infrastructure. Its endeavors have made zero-fossil power days possible in recent years, alongside new partnerships forged with other nations like Japan to advance the global landscape. For this reason, Denmark has developed an association with the wind energy industry that can be likened to Germany and the auto industry. Such a perception of national expertise continues to help its brands such as Vestas to export around the world.

From a brand perspective, greenwashing in the corporate world is increasingly scrutinized by consumers and advertising law. Brand Finance’s inaugural Sustainability Perceptions Index, released earlier this year, demonstrates how a disconnect between perceptions and reality can pose a reputational risk. Regulators continue to capitalize on this momentum, as seen by ambitious disclosure mandates like the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and ongoing consolidation of leading environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting frameworks.

Nation brands are subject to these same market signals. At the 2022 Brand Finance Global Soft Power Summit, Former Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning Schmidt made the key point that nations should be careful to ensure that their communication and applications of soft power are backed up by substance. Further, the enduring power of nation brands must be emphasized; media ‘noise’ rarely appears to register at an international level in the short term, which is why nation branding campaigns must be linked to real substance and supported by long-term financial investment to have the desired effect.

Further Observations on Reputation and Climate Change

One of the Sustainable Futures attributes in the GSPI is Support of Global Efforts to Counter Climate Change. Here, our research indicates misalignment between public perception and reality. The US is ranked at the top, closely followed by the UK. Both nations have been loud voices in climate diplomacy: in the UK’s case, it hosted COP26 in Glasgow and set 2050 net zero emissions targets. However, the contributions of the US and UK to historical carbon emissions and associated climate change are amongst the highest in the world.

Ahead of COPs and other international conferences, the contradictions and shortfalls of participating nations tend to grab headlines. Intuitively, stakeholders question both national intentions and their ability to deliver on the negotiation outcomes. The UK’s recent steps back from its declared net zero plan in autumn 2023 were widely taken up in the media, and its climate leadership positioning was questioned. In a more extreme case, the US and China were not even invited to the UN Climate Ambition Summit held the month prior. These items and more illustrate how relative perceptions and performance can fluctuate and even inhibit participation in key discussions.

Conversely, countries with far lower historic emissions and a lower ongoing per capita impact today are not getting the recognition that they deserve as stores of natural capital. If anything, an infeasible contribution to emissions reductions has been expected from these nations, who have not produced the same emissions intensity nor fully completed their economic development transitions. There ought to be an opportunity for the likes of Sri Lanka, Zambia, Jamaica, Mozambique, and many more to convey the critical role they play in the future climate mitigation dynamics of all nations—and climate conferences like COP are a starting place for this.

—

The upcoming COP28 summit brings a new round of discussion on reducing carbon emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change. Beyond its declared purpose, COP28 is a key space for nations to shape their sustainability perceptions. Through their influence, or soft power, nations can affect the climate commitments of others and boost their perceived sustainability leadership.

When perception is inconsistent with actual climate action, stakeholders are sceptical and reputation suffers: this is seen as the world’s largest emitters continue to face criticism in the international community for lack of execution. COP28 is an opportunity to champion sustainability and build a soft power platform, but gaps between talk and action can destroy it. Comparing expectations for COP28 with its outcomes will be the latest shaping point for national sustainability perceptions.