Last week, Alex Haigh, Managing Director of Brand Finance Asia Pacific, looked at divergent trends in intangible assets across the world. This week, Mr Haigh reviews the consequences of these trends.

“Restarting the Future” by Haskel and Westlake, published this year noted that investment in intangibles is not keeping pace with falls in the investment in tangible assets. This has a number of important effects.

So, what are these effects?

The first point is that, if intangibles are difficult to finance, it will become more difficult to finance companies generally as the relative importance of intangibles grows.

This inevitably has an impact on growth and productivity. As Demmou and Franco note in the 2021 OECD paper “Mind the Financing Gap”, the lack of availability of financing inhibits productivity across sectors dependent on intangibles overall as well as inhibits the most successful firms in intangible-heavy sectors from becoming particularly large and successful.

This knock to productivity means the loss of jobs which tend to be better paid in industries and companies with high intangible value and has been blamed as a core reason for the much slower economic growth in the developed world post-2000 than pre-2000.

There is also a potential loss to the economy and society more generally given the positive externalities that many intangible assets have: by increasing overall knowledge and understanding for example; by facilitating the development of future technologies; or through their ability to create synergies through combination.

There will also be losses for some countries as the value of their ideas is sucked into countries that are better able to finance IP and in others there may be building concentration of power among the select number of firms able to raise finance to support investment in intangible assets.

And why is this happening?

The reasons for there being issues with financing for intangibles are diverse but, on the whole, they relate to: a strong asymmetry of information on their use, strength and value; the difficulty with which they are collaterised - otherwise known as the “Tyranny of Collateral”; and the lack of availability of equity financing which becomes the best form of financing IP given the first two issues.

The asymmetry of information is partly due to the nature of intellectual property. In most cases it derives value only in so far as it can be protected from use by rivals. This protection is created either by keeping the details of secret or by protecting it legally through the use of patents for example. Although patents were once used to showcase innovations while simultaneously protecting it from external use, now that patent litigation is so risky and costly in many markets, even patents tend not to divulge much information of how innovations work.

Other than direct forms of secrecy, more indirect forms of information asymmetry come from the expert nature of innovations and their specificity to individual businesses. The knowledge and understanding of how intangible assets work is within the know-how of the business and, while not necessarily secret, it can be very difficult to understand for non-experts

This means that the core information that investors need in order to invest – valuations – can be difficult to identify and calculate.

Costs incurred are not a great signifier of value because they tend not to have a particularly strong relationship with the value that one can generate from intangible assets and even if they were, it can also be difficult to even identify what constitutes costs incurred on intangible assets.

Identifying potential income can be difficult given the fact that intangible assets are not directly separated from other assets. This is partly because there is not a well developed industry of brand operators and brand owners in the form of licenses in most markets. By developing markets like this, we could help to provide more information on prices. As could a more active approach to separate and commercialise brands internally within companies in the forms of brand companies where the rights and management are centralised.

This centralisation of IP rights seems to be becoming a bit more common as a result of the increased stringency on intracompany payments for intangibles under the OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting framework and benefits from tax amortization like those here in Singapore. However, there will continue to be low public disclosure of the prices used, which generally remain between the tax payer and authority which would need to be addressed.

However, even if this licensing market were to be developed, there is still no real, functioning secondary market for sales of IP rights making it difficult to identify resale value. Ocean Tomo has been trying to run auctions, and other companies have done the same or tried to make marketplaces. IP Bewertungs or the London Intellectual Property Exchange are some examples. However, these are not yet at sufficient scale either to provide strong comparables to make valuation easy – especially bearing in mind the heterogeneity of intangible assets – or to have high enough liquidity to overcome banks’ concerns about using intellectual property as collateral.

That means that most of the comparables you find of sold brands are those sold post liquidation for much less than they were worth as part of the business they operated in.

This you can see with the case of Thomas Cook in 2019. We were valuing the brand – as a value in use by Thomas Cook – at £836m at the start of 2019. By the end of the year and after the company’s liquidation, the brand was sold for the value of £11m. Given the heritage and reputation of the brand in the UK and the obvious licensing potential, this seems like a ridiculously low figure.

Special purpose vehicles have been used in some cases to raise finance for intellectual property by both separating out the legal rights for the IP from the rest of the business and by separating the income from the IP as a license charge in to the special purpose vehicle. This is useful but not widespread and is difficult to price given the lack of a competitive market.

However, despite all of these issues, there is a clear desire to understand intangible asset values. In a 2016 study by Brand Finance, we found that 68% of equity analysts surveyed wanted to see all internally generated intangible assets included on balance sheets.

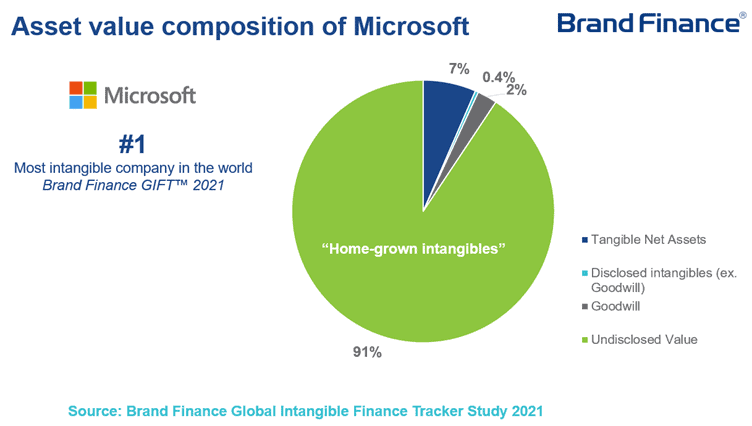

At the moment, only externally acquired intangibles can be included on balance sheets – not internally generated – and even then, externally acquired intangibles can only be impaired downwards, not revised upwards. This means that for the world’s most intangible company, Microsoft, 91% of the value of their intangibles is effectively completely unaccounted for.

Additionally to this, CEOs and CFOs have an incentive not to write down – apart from in the first year of their tenure – given the negative impact on profit which is why we see a surge of impairments when CFO and CEO’s tenures start and a very large reduction afterwards.

If we look at Thomas Cook again as an example, you can see this problem in action. Goodwill clearly needed to be impaired even in 2018 but it wasn’t, giving an unfairly rosey picture of the company.

As a result of this issue, it’s not surprising that in the same 2016 study of equity analysts, we found that 73% of equity analysts want to see intangible assets valued every year and most of those preferred external third parties to do the valuation.

There is some voluntary disclosure. Many companies self report the value of their brands and sometimes their other IP but this is often very skin deep – a dollar value but none of the analysis or explanation that goes behind it. All this means that there is still no particular clarity on where the value is derived from.