This article was originally published in the Global Soft Power Index 2023.

The first commonly accepted definition of sustainability comes from the report ‘Our Common Future’, otherwise known as the Brundtland report from way back in 1987. It succinctly defines sustainability as: “Meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Many sustainability issues go beyond the national scale: the atmosphere obviously transcends the border of any one nation. Emissions released in more developed countries accelerate climate change and endanger marginal agricultural communities in the global south. The illegal wildlife trade in one country risks the spread of infectious diseases on a pandemic scale. Oppressive government and instability create migratory flows that impact other countries.

A country’s commitment to sustainability therefore has clear scope to affect other actors in the international arena, be they states, corporations, communities, or publics, and consequently to influence the preferences and behavior of those actors.

A closer look at our data indicates that there is a relationship between sustainability and Soft Power.

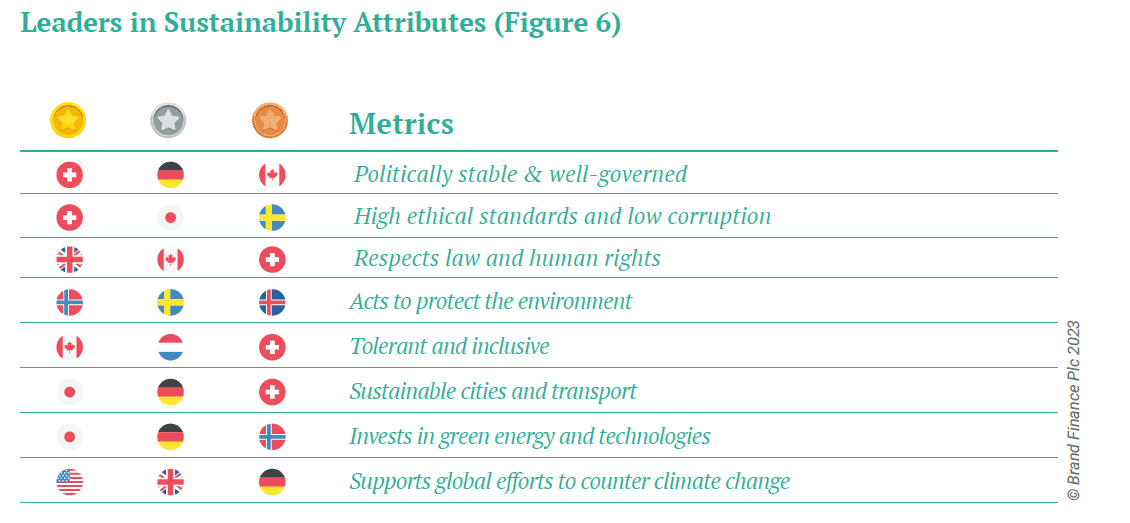

The analysis in Figure 1 shows the nations’ Global Soft Power Index scores (on the vertical axis) plotted against their score on the Sustainable Development Goal Index, an aggregate score on overall SDG progress performance based on dozens of different attributes.

The relationship is not a perfect one, as clearly there are factors such as population, economic power, and cultural influence that play a role, but the correlation coefficient of 0.56 nevertheless shows that there is a clear relationship between sustainability performance and Soft Power.

This year we have enhanced the evaluation of sustainability in our analysis, with a new pillar to capture specific aspects of environmental sustainability. This builds on sustainability-linked attributes covered in previous years. Indeed, all of the following statements that we use to evaluate sustainability could be argued to support one or more of the UN’s sustainable development goals:

High ethical standards and low corruption; Strong educational system; Respects rule of law and human rights; Helpful to countries in need; Strong and stable economy; Politically stable and well-governed; Tolerant and inclusive; Sustainable cities and transport; Invests in green energy and technologies; Supports global efforts to counter climate change; Acts to protect the environment.

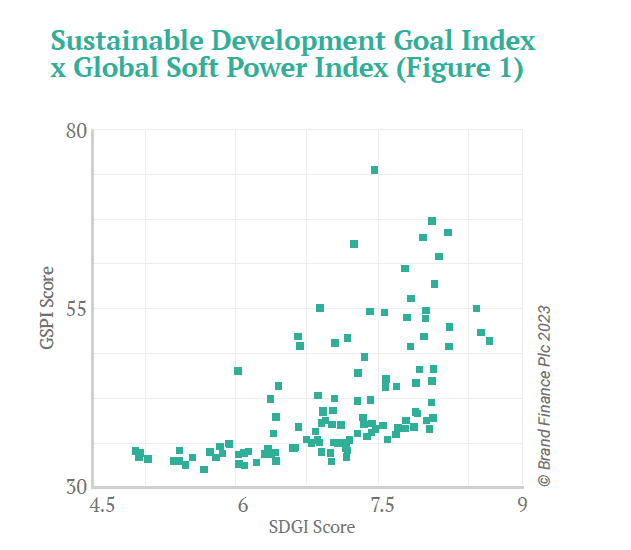

Economic and political stability are understandably core drivers of Soft Power, reflected in their positions as the 1st and 3rd most important drivers of national reputation (Figure 2). More surprising to some will be the powerful role of ‘pure’ sustainability attributes. ‘Sustainable cities and transport’ is the 5th most powerful driver, accounting for 4.6% of influence on reputation, while ‘invests in green energy and technologies’ is the 7th strongest driver (3.9%). These have a far more powerful role than attributes such as ‘influential media’ (1.4%) and even ‘influential in diplomatic circles’ (3.8%).

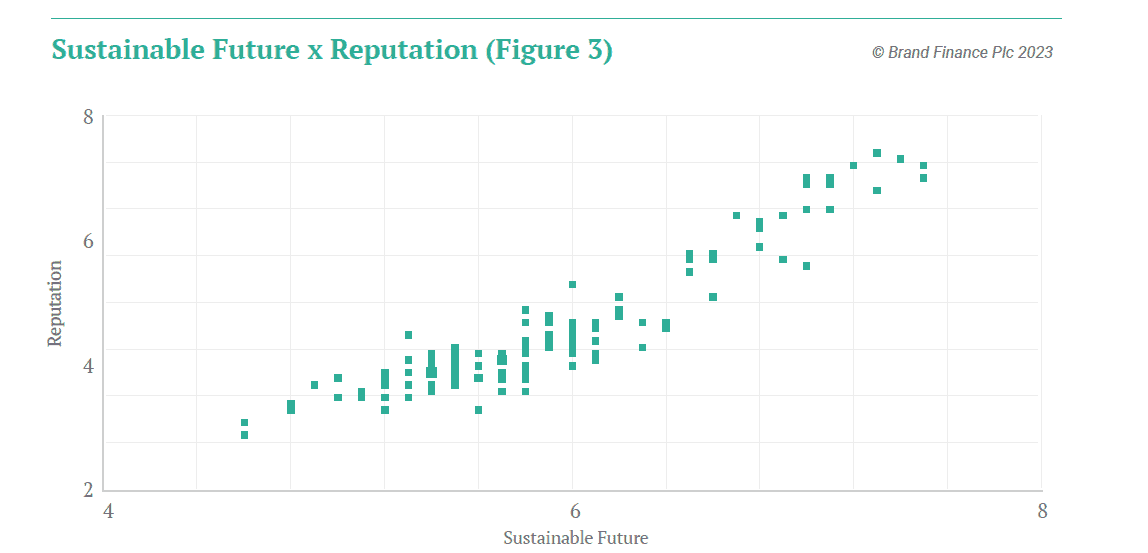

Looking at some outputs from Brand Finance’s online Soft Power dashboard, we can see clear relationships between sustainability and other key components of Soft Power. For example, in terms of Reputation, we see a correlation of r = 0.93.

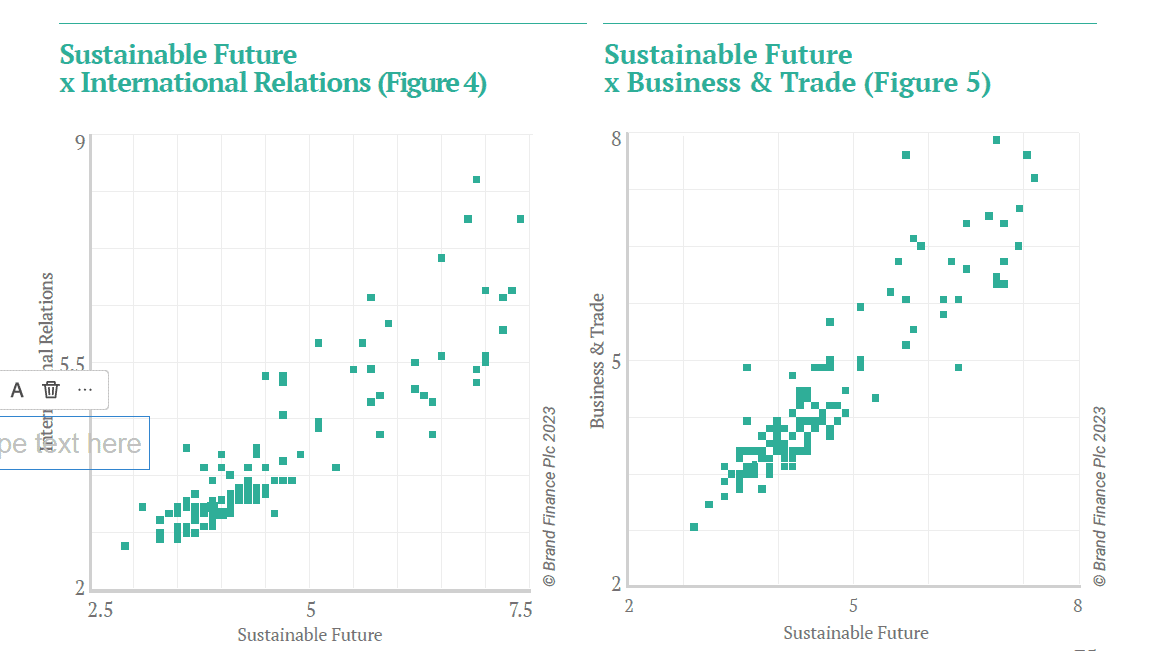

This influence on Reputation would appear to have tangible effects on the application of Soft Power too. There is a correlation r = 0.88 between sustainability and influence in International Relations, and a r = 0.92 correlation between sustainability and Business & Trade.

The five key areas for the application of Soft Power are Tourism, Trade, Talent, Investment, and Diplomacy.

Sustainability in tourism and investment

Tourism is perhaps the area you will be most familiar with when it comes to national applications of sustainability. Typically, these draw on environmental themes around connections with and immersion in well-protected natural environments, as we see from these examples with Australia using its custodianship of the Great Barrier Reef, Slovenia and Peru drawing upon their forests, and South Africa its protection of iconic wildlife.

Nordic countries are particularly strong in both Soft Power and sustainability performance. They are using their reputation for sustainable development to encourage inward investment.

Finland and Iceland both concentrate on their growing role as the locus of technologies that will help to solve the climate crisis, over-consumption and other environmental sustainability concerns.

An interesting example is Costa Rica. Costa Rica has become almost synonymous with sustainable tourism but is increasingly transferring the reputation developed there to inward investment, as they say: “Nature may be Costa Rica’s best-known asset, but sustainable productivity has made it a thriving destination for foreign direct investment.”

And the process seems to be working. Costa Rica’s non-tourism exports have increased in value more than fivefold in the last two decades.

Sustainability in trade and talent

Sustainability has application in trade too. Denmark is another Nordic country with a strong reputation for sustainability based on having been quick to develop a renewable energy industry base and infrastructure. For this reason, Denmark has developed an association with the wind energy industry similar to Germany’s relationship with the auto industry. That perception of national expertise continues to help brands such as Vestas to export around the world.

Sustainability is important to individuals too, and for that reason it is crucial in talent attraction. For example, on Estonia’s talent attraction website the banner image shows its wild landscapes and 3 of the 8 reasons to move to the country are sustainability linked.

Sustainability in diplomacy

The final application of sustainability in a Soft Power context is diplomacy. This is particularly interesting as it is a two-way relationship, and we see national governments exercising their diplomatic Soft Power in order to persuade others to make commitments at major conferences such as COP21 in Paris. On the other hand, these events present an opportunity for nations, particularly the hosts, to present themselves as key diplomatic actors at the heart of events as well as leaders in sustainability.

The relative success of the Paris COP and in particular the Paris agreement create an ongoing association between the French capital and climate action.

One final observation is the Soft Power platform that sustainability can provide to smaller nations that might otherwise be overlooked. Small island states stand to be hit first by the worst effects of climate change and indigenous peoples have long been sustainable custodians of their land – major environmental conferences provide a rare opportunity for their voices to be heard on the world stage.

At the Global Soft Power Summit 2022, Helle Thorning-Schmidt made the key point that nations should be careful to ensure that their communication and applications of Soft Power are backed up by substance.

‘Greenwashing’ in the corporate world is increasingly coming under scrutiny from consumers and advertising law and a disconnect between perceptions and reality can present a reputational risk.

On the flipside some countries are probably not adequately recognized for their strengths on some of the SDG metrics and more investment in promotion or communication could leverage that strength.

Despite repeated use of sustainability themes in communications or reputations as national sustainability champions, many OECD countries are poorly rated on responsible consumption and climate, while African nations are some of the best performers in the world.

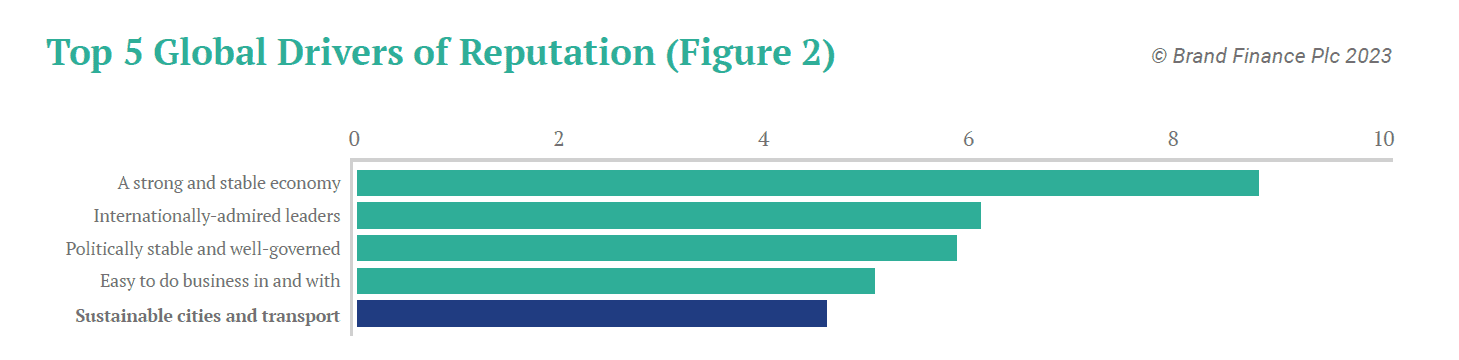

Turning to the nation brand-level results from this year’s Global Soft Power Index, Switzerland scores top on many specific measures of sustainability. for ‘high ethical standards and low corruption’ Switzerland receives the highest score of 7.03, just ahead of Japan on 6.99. Nordic countries, regular top performers on wide range of soft power metrics, also score well. Sweden is 3rd, Norway 4th, Finland 5th, and Denmark 7th (behind Canada).

For a tolerant and inclusive society, we see a similar group of countries. Canada is top, followed by the Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden, and Norway. The top end of the list is dominated by European and North American nations, but Japan is 17th, with South Korea in 28th. The UAE, increasingly positioning itself as a cosmopolitan, international business and tourism hub, has the highest score in MENA, placing 29th.

Some may be surprised to see that the UK receives the top score for ‘respects law and human rights’ following the UK’s complex withdrawal from the EU. It would appear that Rishi Sunak has steadied the ship sufficiently for the UK’s long-established reputation in this area not to have been affected.

This also highlights the enduring power of nation brands; short term ‘noise’ rarely appear to register at an international level in the short term, which is why nation branding campaigns must be linked to real substance and supported by long-term financial investment to have the desired effect.

The United States has the best reputation for ‘helpful to countries in need’. The US’ strong support for Ukraine may help to explain this strong performance, supported by the country’s enduring support for international institutions and development programs. As much as the US is a magnet for criticism, it is clear that global publics recognize and (in soft power terms) reward the country for its generosity.

On measures of environmental sustainability, Nordic countries again perform well. Rated on ‘acts to protect the environment’, Norway is first, followed by Sweden, Iceland, and Finland. ‘

Sustainable cities and transport’ is one of the most important sustainability-linked drivers of soft power. On this metric Japan leads, likely driven by its reputation for exceptional public transportation. Japan is followed by Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland. Interestingly the US is 5th, despite many of its cities being heavily car-dependent.

It is possible that high profile initiatives to improve the sustainability of key cities such as New York (for example the Highline project, the rollout of bike lanes, etc.) has created a halo effect for other US cities. Singapore, the UAE and Qatar also score well on this metric.

The final sustainability statement is ‘supports global efforts to counter climate change’. Here we see clear evidence of a potential misalignment between public perception and (arguably) reality. The US is top, closely followed by the UK. Both nations have been heavily involved in climate diplomacy, including the UK hosting the COP26 Glasgow climate conference and now have 2050 net zero targets. However, the contributions of the US and UK to historical carbon emissions and associated climate change have also been amongst the highest in the world.

Conversely, countries with far lower historic emissions, and a lower ongoing per capita impact today, are not getting the recognition that they deserve as stores of natural capital. There ought to be an opportunity for the likes of Sri Lanka, Zambia, Jamaica, and many more to convey the critical role they will play in the future of all nations.