This article was originally published in the Brand Finance GIFT™ 2021 report.

The majority of intangible assets are not recognised due to the limitations set by the accounting standards boards such as the IASB and the US FASB which state that internally generated intangible assets such as brands cannot be disclosed in a company balance sheet. This is why Brand Finance endeavours to estimate the extent of this “undisclosed intangible value” in our GIFT™ study each year.

Regular readers of the Brand Finance GIFT™ report will be familiar with Brand Finance’s position on the current state of intangible asset reporting. We also spoke to other experts in the field and are pleased to share their views within this report1

Call to Action

Under both IFRS and US GAAP, companies are not permitted to disclose most of their internally generated intangibles on the balance sheet. This leads to an oddity where acquired intangibles are measured and included in the books if they were gained through an acquisition, but the often more valuable internally generated intangible assets are unavailable. This is one factor that leads users of financial statements to disregard intangible asset values in financial statements – they are immaterial and don’t say much about the overall organisation’s intangible value. This oddity can also lead to mismanagement and poor decision making.

"Unfortunately, the ban on assets appearing in balance sheets unless there has been a separate purchase for the asset in question, or a fair value allocation of an acquisition purchase price, means that many highly valuable intangible assets never appear on balance sheets. This seems bizarre to most ordinary, non-accounting managers. They point to the fact that while Smirnoff appears in Diageo’s balance sheet, Baileys does not. They point to the fact that the Cadbury’s brand was not apparent in the balance sheet or reflected in the share price prior to Kraft’s unsolicited and ultimately successful contested takeover of that once great British company. Too many great UK brands have been bought and transferred offshore as a result of this ongoing reporting problem.”

David Haigh, Chairman & CEO of Brand Finance

Brand Finance has long-supported better disclosure of internally generated intangibles. We think that management should undergo an exercise each year to identify and value its key intangible assets. The immediate benefit would be better management, under the old adage of “what gets measured gets managed”.

If management were to take it a step further and disclose their opinion of their intangibles in the notes of their annual report, this would provide greater transparency and reduce the information asymmetry between the market and management.

As with any other element of financial reporting, this information would help to better equip investors with information to guide their capital allocation, so they can efficiently maximise their wealth. In a world where the role of technology, reputation, and customer loyalty is increasing, the time is nigh for a radical shift to improve the quality and relevance of intangible asset reporting.

The Dystopia of Disclosure

Corporates face both legal and financial challenges to full disclosure of all material assets.

“I recognise the utopia where you could have the value of the balance sheet equate to the enterprise value, but I don’t think it is likely.”

David Matthews, President of the ICAEW

One of the main challenges, particularly faced in the UK, is in the restrictive nature of Corporate Governance principles.

“The US is clearly a far more litigious environment, and management teams are in danger of far more draconian civil and criminal enforcement in the US, and yet US management teams are overwhelmingly more focused on taking more risk, because that environment is more permissive to taking risk. And in taking risks, they’re also making greater disclosure. But I think in the US it’s a much more rules-based regime, whereas in the UK, the guidance and the onus is on you to make your decisions, and [the regulator] will decide whether or not to hold you up on those decisions, but [the regulator] isn’t necessarily going to tell you the basis of that decision. And I think that has a strong influence on how management teams feel about the environment, and their subsequent appetite to disclose intangibles.”

Mark Wilson, Former CFO of Aston Martin

The other challenge lies in concerns about the volatility of intangible asset valuation. However, this volatility would bring the nature of financial reporting closer to reality. Share prices are inherently volatile, and therefore it follows that the fair value of assets could and should be sensitive to changes in information.

A further criticism is a question of the consistency and quality of valuations of internally generated intangibles. The concerns are not surprising, taking into account the track record of intangible asset reporting so far, for acquired intangibles.

“When IFRS 13 came in, I was really hopeful that the quality of valuations in financial reporting would dramatically improve and I have been really disappointed because it hasn’t; everybody has looked for ways to group their assumptions, put in weighted averages, pool assumptions from things that are very different and so in the end the reader has no idea what assumptions were made in the valuation process”

Shan Kennedy, Independent IFRS and Valuation Expert and former project director at the UK Accounting Standards Board

For these specific intangible assets that are disclosed, they are generally not relied upon by investors. This is not helped by the little accompanying disclosures of assumptions and methodologies used. In addition, the majority of disclosed intangible value resides in goodwill.

Goodwill itself should only represent the synergies between various assets and between the entities involved in the business combination. All other aspects of goodwill, such as reputation and customer loyalty belong to specific intangible asset classes. But in practice, these specific intangible assets can be undervalued, and goodwill therefore overvalued.

“Practice doesn’t represent what the standard says because goodwill is just smeared into a grey area; it’s too easy for corporates to throw it into the goodwill pot and never do anything with it because they’re not forced to. […] The key is pushing people into greater disclosure and forcing boards into a more critical view where today they don’t need to.”

Mark Wilson, Former CFO of Aston Martin

As discussed at length in "What Went Wrong With Carillion? The Accounting Treatment of Goodwill", a further issue with goodwill is that companies do not impair it as frequently or as significantly as market conditions suggest they should.

In the two years leading up to Carillion’s collapse, the reported level of goodwill exceeded the total enterprise value of the company. Since 2011, goodwill represented at least 84% of total business value. However, during this time, Carillion did not impair its goodwill, allowing retained earnings to remain stronger, and thus facilitating pay-outs such as executive compensation.

Goodwill Impairment in Practice

Carillion is not alone; analysis conducted earlier this year found that only 10% of entities with goodwill reported took an impairment against goodwill in 2019. And among the handful of entities where goodwill has represented more than the total value of the company for 2 years running, only 27% of those companies took a goodwill impairment in 2019.

You may feel that while impairment may be an infrequent occurrence, these impairments - where the carrying amount of goodwill exceeds total company value -should be larger, but our analysis suggests that the size of an impairment cannot be predicted by how large a company’s carrying value of goodwill.

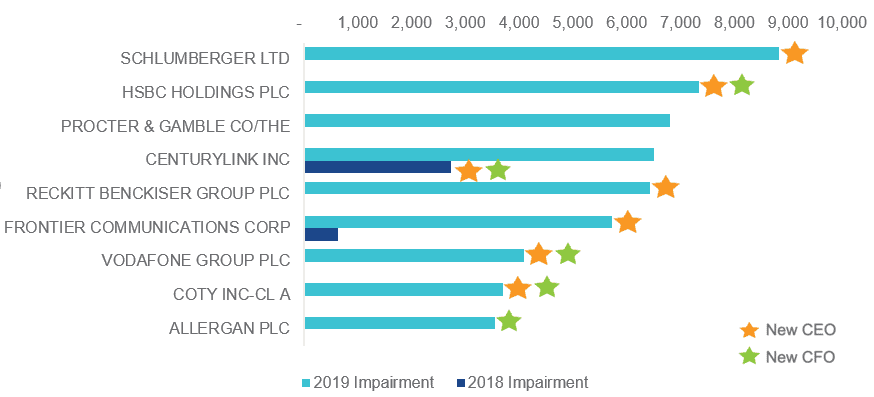

One thing that 2019’s largest impairments do seem to have in common is new leadership. 2019’s largest impairments are summarised in chart 9.

Except for Procter & Gamble and CenturyLink, all companies listed had either a new CEO, a new CFO or both in 2019. The majority of these companies’ previous leaders decided to not take an impairment in 2018. CenturyLink did take an impairment in 2018, when it also had both a new CEO and CFO.

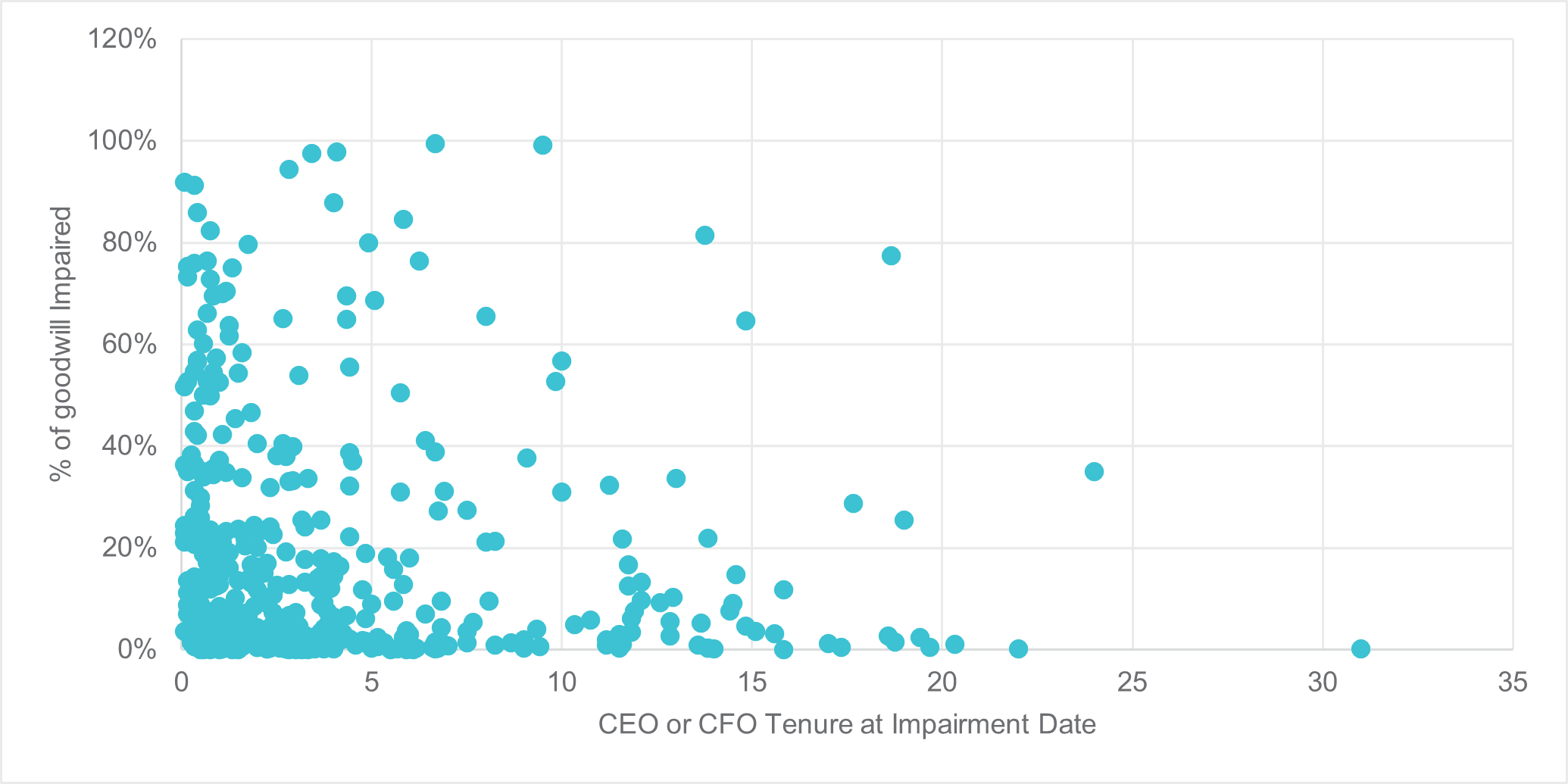

Therefore, new leadership appears to have a significant impact on the likelihood a company will impair its goodwill. Among the entire sample, we found that 30% of all impairments occur within the first year of having a new CEO or CFO.

For larger impairments, where the impairment represents at least half of the goodwill carrying amount, 41% of these occur within the first year of new leadership.

At best, this analysis suggests that goodwill impairment can be influenced by varying personal opinions of management personnel and their perceptions of outlook and risk.

At the worst, this analysis suggests that there may be an ulterior motive within the decision to impair goodwill. By taking an impairment at the beginning of your tenure as a CEO or CFO, it helps you to a) set a precedent that suggests your predecessor was negligent/ overoptimistic about their acquisitions, or b) influence the share price to fall initially then rise throughout the rest of your tenure.

If this evidence is simply reflective of varying personal opinion about business outlook, it suggests that the goodwill impairment process is not objective. In fact, this critique has been raised regularly to the IASB during the post-implementation review of IFRS 3, the financial standard concerning business combinations.

In March this year, the IASB released a discussion paper on the topic of goodwill impairment due to the feedback received from both preparers and users of financial statements. The users’ feedback is that goodwill impairments provide very little information as they are “too little, too late”. When impairments do occur, it confirms what investors already suspected, rather than providing useful, timely information on the performance of acquisitions.

While impairment is preferred to amortization by the majority of the IASB, it is widely recognised as flawed in practice, due to the subjectivity of the impairment process. So how could goodwill impairment practices be improved to ensure timely impairment of goodwill? An overwhelming request, from experts and from investors, is for greater disclosure surrounding the reporting of both goodwill and other intangible assets.

“I think the framework is there to get it right although it does depend on people being very diligent about what they do and very objective about [...] how the acquired business is actually performing - whether or not it is in line with what you originally thought when you recorded the goodwill – as well as considering the future overall economic outlook and whether your plans for the business are changing. A lot of it comes down to [...] being as objective as you can- even those people who made the decision to acquire the business and have a vested interest in a positive result."

David Matthews, President of the ICAEW

Regarding the specific intangibles which are disclosed alongside goodwill:

“There should be a proper description of what has been valued in each case, what it does and how it provides value and how its life has been assessed; so [for example], what is this technology, is it a grouping of several pieces of technology or is it just one very specific piece of technology?”

Shan Kennedy, Independent IFRS and Valuation Expert and former project director at the UK Accounting Standards Board

Of course, there are model cases of impairments that provide useful information to investors, even if just from a qualitative perspective. In the case of Procter & Gamble, the 2019 impairment demonstrated in chart 9 was part of an US$8 billion impairment to Gillette goodwill and brand value, due to a worsened outlook caused in part by increased competition from disruptive players such as Dollar Shave Club.

While most investors were already aware of this competitive threat, the impairment and accompanying disclosures provide both confirmation of the threat, and informs investors that management are both aware of and acting on that threat.

The Way Forwards

It seems that narrative reporting can be improved relatively simply, by better communication between preparers and users of financial statements, who should make their demands known. A further area for improvement is in the disclosure of quantitative valuation assumptions applied both in impairment testing and intangible asset valuation.

This request is of course more complicated, as preparers of financial statements may be concerned about the scrutiny they may face over their selected assumptions. And those assumptions can have a wildly material impact on the resulting valuation. After time the process would become simpler and could improve the quality of the underlying valuations.

“If there were better disclosure of the figures that had been used, and this applies not just to impairment but to valuation generally, the whole quality of valuations in financial reports would improve dramatically and we would also start to get alignment and consistency across different companies because people would take a look at what their competitors were doing.”

Shan Kennedy, Independent IFRS and Valuation Expert and former project director at the UK Accounting Standards Board

Furthermore, organisations such as the International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC) could play a role in improving the quality of intangible asset valuation. Through years’ of experience, the Brand Finance team have developed standardised approaches to valuation, and were major players in the development of ISO 10668 and 20671 - the international standards on brand valuation and brand evaluation. Other valuation standards also provide guidance on the approach to valuation.

We are now in a pivotal moment for the future of intangible asset reporting. In March 2020, the IASB released a discussion paper on the post-implementation review of IFRS 3, focusing specifically on goodwill and impairment. In the ongoing 3rd agenda consultation, the IASB must determine how to address the topic and the specific projects required surrounding intangible assets.

The IVSC has relaunched the IVS this year, providing updated guidance on intangible asset valuation to practitioners. Intangible Assets (IVS 210) is one of eight asset-specific standards. The latest version of the Standards brings greater depth to the IVS, as recommended by member organisation, including the major accountancy firms and Valuation Professional Organisations.

Change is on the horizon, and we are optimistic about the future of intangible asset reporting.

Brand Finance has been lobbying for greater intangible asset disclosure for about 20 years now. The IVSC supports Brand Finance, and all others, that look to make progress on this most critical issue.

Kevin Prall, Technical Director, IVSC

Recommendations

In an ideal scenario, boards should produce a fair valuation of the business and its constituent assets at each year end- both tangible and intangible. The results should be disclosed in the notes to accounts, and therefore made public to remove information asymmetry. In our view, these valuations should be conducted in line with IFRS 13 (fair value measurement), and by independent practitioners appointed by the board in order to minimise risk to the board members. This concept is not radical; it is akin to portfolio valuations conducted annually by investment trusts and private equity funds about their invested companies.

In order to increase confidence in intangible asset valuation and increase the feasibility of our ideal scenario, there should be better disclosures about impairment reviews and intangible asset valuations. Both the qualitative narrative and disclosure of quantitative assumptions can be improved. For quantitative assumptions, the first step is to disclose the specific assumption used and reduce or eliminate the practice of disclosing ranges of assumptions.

- Please note that the views expressed in this report are of the individuals and are not necessarily the official views of the organisations that they represent.[↩]