A robust measure of brand equity is strategically crucial for any branded business.

It may sometimes be difficult to quantify and there is no 100% consensus on how to measure it, but every business needs to develop a system for assessing whether their brands are healthy, enjoy a strong and resilient reputation, and most importantly, are poised to deliver future growth and commercial return.

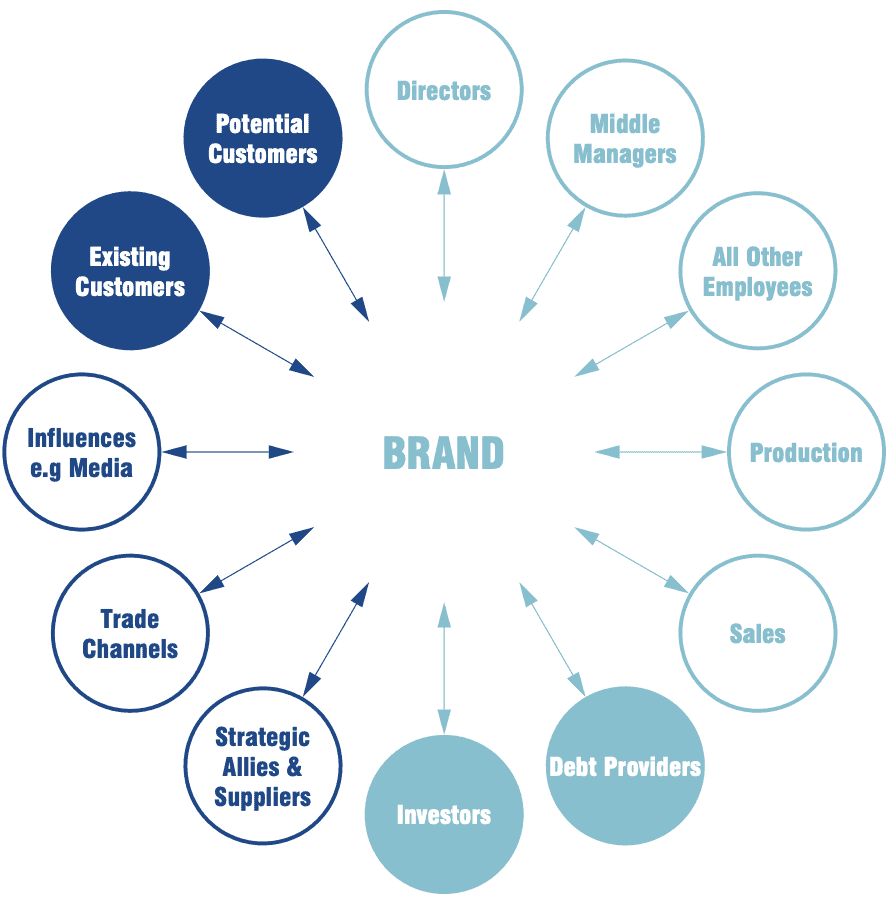

A comprehensive measure of brand equity sits at the heart of brand evaluation. This means measuring the degree to which stakeholders are aware of the brand, and their perceptions of it.

Each year we conduct our own global consumer equity research study in over 20 sectors and 30 geographies.

Brand Equity Research Method

Most (but by no means all) brand owners measure brand equity or brand image in some way. In many cases, the core of such measurement is some form of market research to survey the opinions of customers/consumers, and perhaps other stakeholders. However, other data sources and signals may also have a role:

- Comments and reviews in online social media and other online media.

- Customer complaints and other direct feedback.

- Transactional or behavioural data, e.g. a number of website visits, retail footfall, search volumes, etc.

- Feedback from sales teams and other on-the-ground staff.

The voice of the customer is essential, and while signals from social/ digital media are valuable (and meaningful), they are not sufficiently comprehensive and reliable as measures of brand equity. Therefore, robust surveys of relevant stakeholders are still fundamental to brand equity measurement.

Do We Rely Too Heavily on Surveys?

In recent years, some marketers have challenged the reliance on survey data at the core of brand evaluation. They are seen by some:

- As a ‘rear-view mirror’ - i.e. too retrospective.

- To reflect sales and usage experience, but neither drive nor predict sales.

- As ‘over rational’ (“consumers always lie in surveys”)/

- To not take into account the ability of brand owners to ‘nudge’ consumers to purchase their brand regardless of underlying feelings.

- As not fast enough, in a world where other signals/data are available in real-time.

- As expensive/impractical for some segments or audiences.

Such views understate the degree to which survey measures are predictive of future behaviour/outcomes. There is convincing empirical evidence that improvements in survey scores do lead to higher sales and other commercial gains (though there is certainly dual causality evident, too). Noted academic and marketing scientist Koen Pauwels concluded “attitude survey metrics excel in sales prediction”1

Customer/market surveys are rarely ‘perfect’, but they are valid solutions for evaluating brands.

Input and Output Metrics

When evaluating brands, one should look to use both input/investment and output/performance metrics. Input measures reflect the degree to which a brand owner is investing in and supporting the brand. These are, therefore, forward-looking and less about how the brand may have performed to date. Typically, one should consider:

- Marketing investment: for example, ad spend, social media presence and activity, search, events.

- Product investment: for example, brand-related R&D and innovation, number of patents.

- Existing systems and processes: such as quality management systems.

- Service performance: where this can be objectively and independently measured, can also be incorporated – for example, airlines’ punctuality performance.

- Physical presence and resources: number of branches, staff or other tangible resources.

Outcome measures such as sales, market share and profitability will be familiar to all brand owners, and obviously form part of any overall brand evaluation. Price elasticity or ability to sustain price premiums is an often-overlooked measure in this space, particularly in categories where price promotions and discounting is commonplace.

Many would consider these to be the result of a strong brand and investment behind it (i.e. the inputs and outputs above), and therefore on their own are not adequate measures of brand strength. Moreover, sales may be up or down for a variety of other factors (market/economic conditions, regulatory issues, etc.), and hence do not necessarily reflect the underlying health and strength of a brand. They should, however, always be considered.

Which Stakeholders to Survey

Most brand owners start by wishing to understand how their brand is perceived by their customers – as the old adage says, the customer is king. This would be our recommendation, though we should consider:

- Coverage: it is not good practice to survey only your customers (or people in your CRM database). It is essential to get a ‘market view’ – perceptions of your brand from both customers and non-customers.

- Intermediate parties: the relevance and impact of other opinions in the sales channel/process: brokers, retailers, etc. For example, an over-the-counter healthcare brand may need to gauge the views of pharmacists and doctors as well as consumers/patients.

- Demographic and Geography: there is often a need to cover specific customer/market segments (demographic, geographic, product-line, etc.)

- Internal users/influencers: In complex (typically B2B) purchase decisions, recommenders are a crucial stakeholder in the sales process.

In addition, depending on the brand and budgets available, it may be relevant to ascertain opinions about the brand among:

- Employees (and possibly potential employees)

- Regulators and other public officials

- General public: to track your broader corporate/brand reputation

- Media figures and/or other ‘influencers’

Typically, some trade-off will need to be made with regard to stakeholder coverage and budget/ frequency. For example, a multinational brand manager may face the question: is it more important to cover end-customers in every country in the world, or to survey the views of retailers in my five key global markets?

What to Survey

Much has been written on this subject, and many major market research agencies have standard brand equity tracking frameworks incorporating standard evaluation measures. Though there are some differences, there is broad consistency in the main dimensions to cover.

The exact mix should only be chosen after gaining a full understanding of the branded business, its market dynamics and strategic goals. Equity tracking typically features brand KPIs which summarise people’s overall opinions and feelings towards a brand, and the extent to which they are familiar with it. These should generally include:

- Awareness and familiarity

- Consideration &/or future purchase intent

- Preference

Together these three form the ‘brand funnel’ – measures which sum up the market presence and position of a brand. Much evidence suggests that consideration is the most powerful measure of these. Most brand evaluations will also include a combination of these measures.

- Overall evaluation: overall opinion/reputation/relevance – this might be ratings of the brand on straightforward questions, or a more ambitious attempt to capture emotional responses/feelings via less direct questioning or even biometric responses.

- Recommendation/advocacy: most commonly the Net Promoter System (NPS) which is a widely-used measure of customer satisfaction/recommendation. However, there is a good case for measuring actual levels of recommendation (or word-of-mouth) in addition to recommendation intentions via NPS.

- Quality, trust, value for money. In some cases, a composite metric which combines all relevant measures into a single index score; this can be helpful in summarising overall performance/progress.

Key Principles When Designing a Brand Evaluation

Brand KPIs should be commercially-validated, not ‘vanity measures’. Most of the above have been validated in some way – i.e. an increase on a given measure can be expected to translate into an improvement in sales, market share, willingness to pay a price premium, customer loyalty, etc.

Brand owners should ascertain the relationship between brand KPIs and their own commercial outcomes – generally via complex analytical modelling, but if not at least a conceptual model of why such a measure is commercially impactful. Likewise, KPIs should relate to brand inputs in a meaningful way. It is important that KPIs are sufficiently sensitive and responsive to measure marketing ROI and campaign effectiveness. Marketers need to know which actions will impact the brand.

KPIs should be aligned to brand/business strategy – for new/ emerging brands this might place greater emphasis on word-of-mouth or opinions among ‘influencers’, for example. But the core metrics above are relevant to most brands. Avoid data overload – don’t just measure everything because it can be measured. Consider the number of KPIs that provide genuine insight, or can be communicated to internal stakeholders, especially senior management.

Some of the ‘overall evaluation’ measures can be highly correlated with each other, and resource is wasted measuring virtually the same thing in 2-3 different ways. Current trends are for big brand owners to highlight a smaller number of KPIs which best predict future outcomes, and reduce duplication. KPIs must have credibility and comprehension beyond marketing/ communications teams. Consistency is important – KPIs need to be tracked over time.

Alongside the brand KPIs will be a range of diagnostic and analytic variables, where time and budgets permit – for example detailed brand image ratings, profiling variables (demographics, brand purchase history, etc.)

Budgetary constraints clearly play a part – there is little point spending $1m/year evaluating a brand whose revenues are at a similar level. Where brands or budgets are small, it may be difficult to conduct an evaluation as thoroughly or frequently as desired – but it is possible to obtain very basic measurements for just a few thousand dollars per year.

Non-Survey Measures

Survey measures should be integrated with other data signals of brand performance. These might include:

- Social media analysis: generally of volume and sentiment of posts and mentions about a brand; such analysis should cover as many social channels as possible (i.e. not just a brand’s own social channels, but a full range of social media, blogs, news sites, etc.). This should never replace survey measurement. All evidence indicates that to evaluate a brand rigorously, social media data alone is insufficient, even for brands targeting young people or heavy tech users.

- Search volumes/trends: particularly organic search. There is increasing empirical evidence that the share of search is an important indicator of brand strength.

- Review scores: which are obviously more relevant in certain categories such as travel, tourism, and restaurants.

Measurement and Reporting Frequency

Brand evaluation should be focused on assessing the underlying health of the brand, which for many mature brands evolves relatively slowly (unless there is a corporate scandal or genuinely breakthrough innovation). Hence measurement is generally geared towards relatively stable metrics which change slowly over time – consideration, overall reputation, trust, etc.

But marketers always want the most up-to-date measures, and in addition, there may be a need for frequent or continuous evaluation - e.g. to assess the impact of short-term or tactical marketing activity on brand measures.

The need for relatively expensive, ‘continuous’ tracking (with monthly reporting of KPIs which hardly differ) must be assessed carefully. For even fast-moving categories, quarterly tracking may be more than enough, and for many sectors, annual tracking will suffice.

There is no need to design a one-size-fits-all system. Smaller brands or markets can make do for lower frequency, and some evaluation systems focus on frequent KPI measurement coupled with less frequent ‘deep dives’ into brand image. And as with survey content, measurement frequency should be determined once the needs and culture of the business, and its strategic goals, are established.

Lastly, the use of non-survey measures such as review or social listening data can often fill the gaps between survey measurement periods, as these data streams are often real-time.

Reporting and Dissemination

The value of Brand Evaluation is only maximised if the results and strategic implications are widely shared to people that can act on the findings. The degree of detail and frequency must be tailored to the audience, and it is helpful to have a strategy following principles such as these below:

The reporting plan will reflect the organisational structure and culture of the brand owner – there is no set formula. But typically, senior management needs (and should be encouraged to focus on) a relatively small set of KPIs, and reporting frequency that is both insightful and actionable. The goal should be to avoid the trap of monthly reporting which concludes “it might be a blip, let’s see what next month looks like…”.

Importance Weights and Driver Analysis

A key requirement of any model is to ascribe a weight (or measure of importance) to each element, which may not be easy. Ideally, weights are derived via statistical analysis of input and output data, and within input data such as customer surveys. The latter involves conducting ‘driver analysis’, determining the likely impact on customer choice/consideration which might accrue should performance improve on an individual element (e.g. ‘innovative products’).

Of course, surveys can get people to say directly what is important to them in making their brand choices (‘stated importance’), but this approach is generally regarded as delivering over-rationalised results. Ideally, the stated importance should be assessed alongside statistically-derived importance before weights in the evaluation model are calculated.

In our model we use a combination of stated and derived importance analysis in its BSI Evaluation framework, and wherever possible sets weights based on their observed impact on brand revenues and value.

Data Sourcing

Identifying suitable data sources, and assessing its quality are important parts of the evaluation process.

Not everything that can be measured should be, and perfect measures on every dimension cannot necessarily be obtained. Even the very largest organisations have to make trade-offs in respect of data coverage (markets, stakeholders), precision, timeliness, etc.

Factors to consider:

- What data is already available internally or externally – do we really need to commission further research?

- Are there good proxy measures available for a specific dimension?

- How quickly are measures likely to change? Is data from a year or two ago suitable?

- If detailed data is not available, are the views of industry experts/ analysts a good substitute?

Conclusions

It is perhaps a no-brainer that the best brand strength evaluations are ones that thoroughly consider all the relevant brand attributes. Due diligence is so crucial when evaluating your brand.

When setting out to evaluate the strength of your brand it is often useful to have an experienced hand at the wheel, so that the exercise can be run smoothly over many years. A perfectly balanced brand strength scorecard will be the strongest tool in a marketers belt.

Brand Evaluation 101 Why Brand Evaluation Is An Important Management Practice Measuring Brand Equity The Brand Strength Index (BSI) - Our Brand Evaluation Process

- K.Pauwels and B. van Ewijk, 'Do Online Behaviour Tracking or Attitude Survey Metrics Drive Brand Sales? An Integrative Model of Attitudes and Actions on the Consumer Boulevard', Report No. 13-118, Marketing Science Institute, 2013[↩]