This article was originally published in the Brand Finance Football Annual 2020.

The growing appetite for European football among US investors has been gathering momentum for some years, adding to the plethora of foreign owners that have been drawn to the game in England and other major football markets.

Over 17% of English clubs have some form of US ownership, either 100% such as Manchester United, Liverpool and Arsenal, or a minority stake such as Leeds United and West Ham United. American money has started to make their mark in Italy at AC Milan, Roma and Fiorentina, while in France, Marseille and Bordeaux are majority-owned by Americans.

Mature

Sports investment is a mature business in the US and wealthy owners see the sector as an opportunity-rich industry that can attract huge corporate sponsorship, significant broadcasting revenues, and networking possibilities that can extend global franchises and open-up new avenues of business.

Indeed, in the US, team owners are often highly revered figures (especially if the team is successful) and frequently the first person to receive a major trophy at the end of a play-off or final is the owner. In Europe this is seldom seen, although when Chelsea won the UEFA Champions League in 2012, club owner Roman Abramovich was visible in the presentation zone holding the trophy aloft. In some countries, club ownership is regarded as a thankless job for thick-skinned and wealthy business people.

US investors differ from other contemporary football club owners. American high net worth individuals have long identified the positive revenue generating trajectory of their own sports industry – American [gridiron] football, basketball, baseball, and ice hockey, not to mention the recent addition of Major League Soccer. Enhanced by the US model of closed leagues with no relegation, as well as big broadcasting revenues and substantial consumer expenditure, rewards can be significant through medium-to-long term involvement.

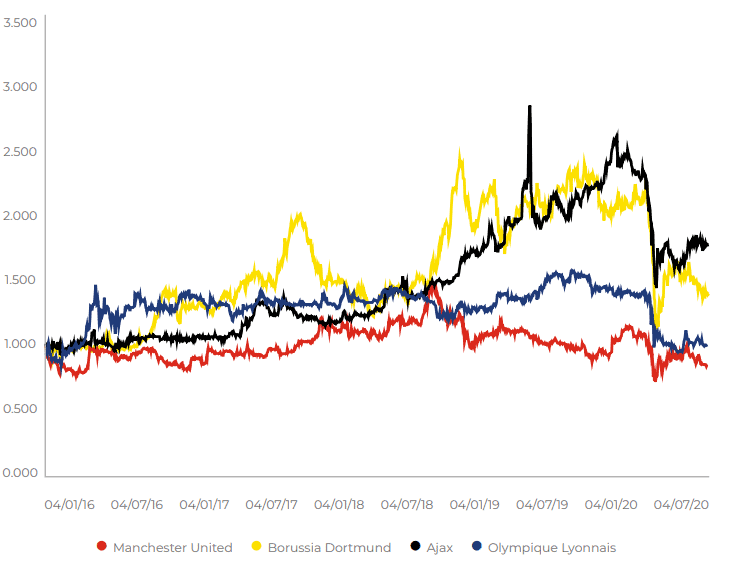

Football has become an asset class in its own right, with investors using sophisticated financial market tools to execute their acquisitions. In the case of the Glazer family’s purchase of Manchester United, they put up a percentage of the £ 790 million price themselves but the majority came from borrowings that were loaded onto the balance sheet of the club – a leveraged buyout.

The modern football paradigm in Europe often appears to have a short-term outlook, so supporters invariably look for “quick wins” when a new owner moves in on a club. For US owners, financial performance is of paramount importance, primarily for the dividends they can yield, but also due to stability and sustainability reasons. This is in notable contrast to those that spend large sums on the club in order to achieve instant success and profile before selling their stake.

Approach

US investors invariably fall into the category of owners that want to maximise their gains – in other words, it is a financial transaction as much as a sporting deal. Philanthropy has little to do with it. This is unlike some investments made by wealthy individuals who want to put something back into the club they have supported all their lives or the strategic investments made to gain political ground, such as those at Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester City in recent times.

The US way doesn’t necessarily mean the owner is popular among fans who expect “ambition” to be shown in the form of vast outlay of cash to bring headline-grabbing talent to a club. However, in European football, there are many clubs who are prepared to spend big in order to remain competitive and stay ahead of rivals. Hence, a club that is slow to spend can fall behind its peer group. This does create the dilemma of a club liberal stance around team-building. At the same time, the owners may appear to be satisfied if the club’s balance sheet looks healthy and they are receiving satisfactory returns. A certain level of on-pitch success is needed to maintain that vision, however.

Given US sports operate in a closed environment with financial restrictions, the threat of relegation is never something that creates anxiety or intense pressure to spend. Conversely, in the case of English Premier League clubs, relegation from a league that has extraordinary broadcasting revenues can appear tantamount to a death knell. This explains why the constant drive for status preservation and team reinforcement characterises leagues like the Premier League and doesn’t allow for inactivity on the part of a club and its owner. Needless to say, the open market and “survival of the richest” culture of European football can be a deterrent.

While the US approach to sport may not be to everyone’s liking, it is widely acknowledged that US sports franchises are generally well run, well-resourced and relatively conservative. Moreover, their stadiums are invariably comfortable, scalable and commercially successful.

Learn more about foreign ownership and football sponsorship here or get in touch using the form below to discuss your options.

Understanding

Traditionalists and sceptics explain the reluctance to satisfy the crowd and behave recklessly as a sign that US club owners do not have an historic understanding of football. Owner visibility is important to European fans, especially in the United Kingdom, although the investors, for whom the football club may be part of a portfolio, would often claim they pay people to run the club for them. Hence, at Manchester United, Ed Woodward, a former investment banker, is very much in the firing line with the public and receives considerable criticism from fans, notably through social media.

The success of Liverpool, around a decade after Fenway Sports took over the club, demonstrates that a degree of patience and strategic acquisition can create consistent success. There has been no lack of investment in strengthening playing resources at Liverpool, indeed the 2019-20 Premier League champions have a squad almost as costly as heavily-financed Manchester City, although their net expenditure is among the lowest in the league.

While Manchester United have undoubtedly declined since the departure of Sir Alex Ferguson and Arsenal have struggled for a clear identity in the post-Arsene Wenger era, Liverpool appear to be on the brink of a golden new era to rival their trophy-laden past. But Arsenal and Manchester United’s malaise may be less to do with their US ownership than the natural cycle of football and a lack of succession planning, which once more hints at football’s lack of foresight in looking beyond the next piece of silverware.

US investors are certainly not short-term partners and are almost always looking at a long and sustainable involvement. They demand success, but not at the type of cost that threatens the stability of their assets.