Analysing Brand Strength and why it matters

Every day at Brand Finance we are tasked with evaluating the strength of brands and marketing and valuing the impact of that strength. Within that task lies a requirement to answer different layers of questions including:

- What is a brand and what makes it strong?

- Why do brands and brand strength matter?

- What are the most popular brands?

- What can you do to build Brand Popularity and Strength? – The Brand Beta model

The following series of short articles is intended to explain how we do that and what that means for businesses.

4. What can you do to build Brand Popularity and Strength? The Brand Beta Model

At Brand Finance, we spend our time analysing the impact of brand reputation on financial performance and on how businesses can use marketing spend, brand strategy and other tools to maximise that impact. We therefore feel we are in a uniquely privileged position to identify what drives people towards choosing one brand rather than another.

As we have established previously through our Brand Beta analysis, brands are able to impact the performance of a business firstly if they are well known and understood and secondly when they command certain perceptions in people’s minds that positively influence their likelihood to purchase or interact with them.

There are different models to explain this, some more complicated than others. However, as I’ve mentioned, in general there are two core points driving the popularity and therefore growth in brands.

- Awareness and Recall at the point of sale or consideration

- Relevant/Meaningful Differentiation while considering.

Our Brand Beta analysis has shown the first point to be approximately twice as important as the second. However, there continues to be argument about this relative importance.

In particular, there is contention over what constitutes relevant differentiation. This is why I have made the deliberate distinction between functional and emotional differentiation in the model below since the ability of brands to differentiate on emotional factors is an area of dispute.

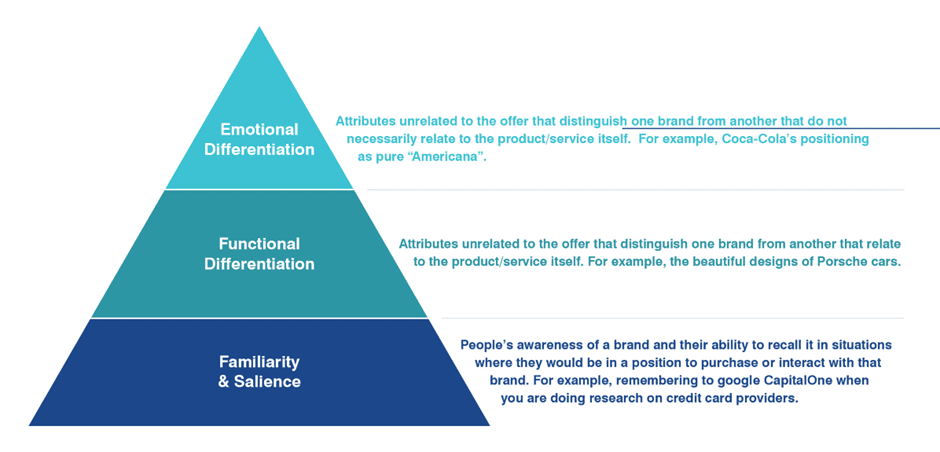

Title: The Brand Strength Pyramid. Source: Brand Finance

At the foot of the pyramid is familiarity and salience.

Salience refers to the situation whereby the brand is immediate to the mind of people at the point when they would choose that brand over others. While this represents something a little beyond brand familiarity, it is related concept and encompasses general awareness too.

As Jenna Romaniuk, Byron Sharp and the rest of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute point out[1], this Salience is often created and reinforced by brands that are distinctive – i.e. easily distinguishable in people’s minds from other brands – as opposed to differentiated. That is, that they have “assets” – for example slogans, colours, patterns, sounds, mascots etc – that help them be more memorable and easier to distinguish. These assets only become powerful and distinctive through continued, consistent use where they are widely seen by the public. In particular, where these assets are widely advertised or promoted over a long period of time.

The implication of this is that products and companies should not change their slogans, mascots, designs etc too often. Assets that are imperfect but consistent and well known may be more powerful than a modernised design or a strapline which explains slightly better the purpose or new positioning of the brand.

Additionally, companies and products should be rebranded as infrequently as possible. Even minor name changes create big mental inconsistencies that are often difficult and costly to recover. A full name change in particular is more often than not a significant destroyer of value.

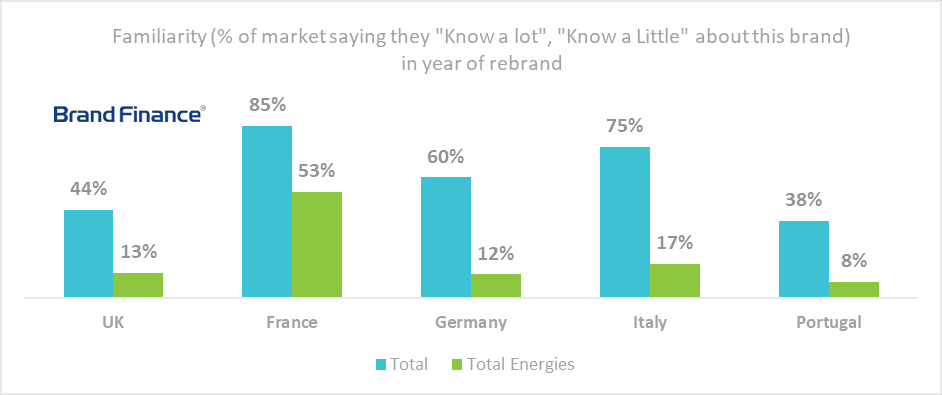

You can see this effect in the recent rebrand in 2021 of TOTAL to TotalEnergies. What seems like a small change was not widely understood by the public. Taking a sample of 5 European countries, we found that in the year of the rebrand there was significantly lower familiarity towards the new brand despite it being widely used. Over the following year, large amounts of investment were needed to build familiarity back up to its previous level.

Source: Brand Finance Global Brand Equity Monitor

The exceptions to this destruction of value are where the company is rebranded to a brand that is (or will very soon be) better known and liked than the one it is replacing or where the company is associated with a scandal so great that its brand is irreparably damaging to the business. Although in the latter example the irreparability criterion is rarely reached.

Additional to consistent, widespread promotion, our own previous work on this subject for clients finds that these assets are significantly more effective when they are applied to a high standard. For example, where petrol forecourts are appropriately painted and the brand identity properly applied, we have found significant uplifts in demand compared to those forecourts with the same brand but a visual identity applied to a lower and less consistent quality.

Moving beyond salience in the pyramid, there are the two types of differentiation “Emotional” and “Functional”.

Additionally to being distinctive, brands are strong because they are associated with positive attributes of the branded offer. These attributes can relate to both the functional qualities of the product or service offer or they can relate to more emotional attributes (like the positive perceptions of being independently owned or saying something about one’s own self-identity). In both cases, these are assumed and therefore not totally rational.

These areas of differentiation can be found via market research and plotted on a correspondence map to identify relative positioning of each brand. It is worth doing so in order to identify what is driving customer purchase among different target audiences and where a specific brand is doing well or badly.

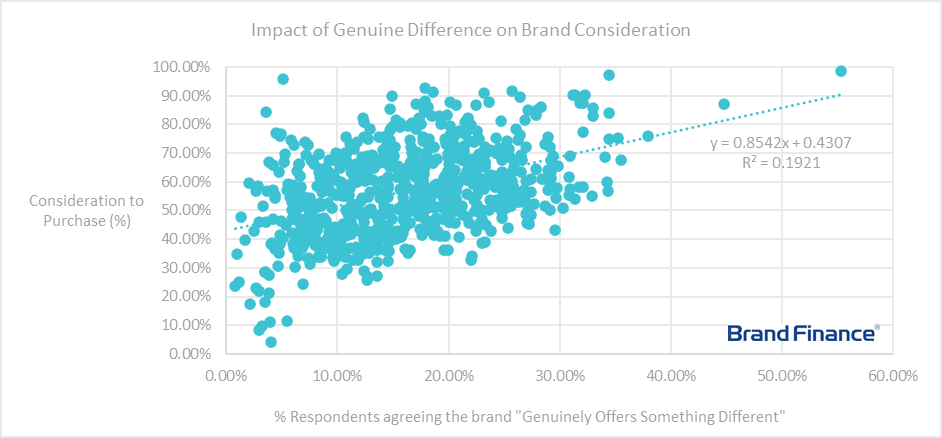

However, it is easy to overstate the importance of being different. Using the banking industry as an example, Brand Finance’s Global Brand Equity Monitor study of 722 banking brands in 35 different markets, we find a weak relationship between the percentage of respondents who say the brand “Genuinely Offers Something Different” and their consideration to purchase.

Source: Brand Finance Global Brand Equity Monitor

The graph above plots % of respondents agreeing the brand “Genuinely Offers Something Different” versus their consideration to purchase. We note a positive relationship but one where this measure only explains 19% (0.1921) of variance, indicating a weak relationship.

Additionally, many of the brands that strengthen the relationship are fintech brands like GCash a payment service in the Philippines or Revolut – a British Fintech company – which do not, in any case, offer a full service banking offer. This means that being genuinely different is an even weaker predictor of choice in banking than the graph suggests.

But before you say that banking is a particularly unique industry in within which people value steady predictability, we have found this relationship in other sectors too. Having completed this analysis also on the car industry across the 18 markets we research, I can confirm that the relationship is no stronger there. Only about 18% of variance is explained by this measure.

In reality, this is unsurprising. The biggest and most popular brands will come to dominate the market, begin to resemble it and therefore no longer be different. Difference is the victim of success. Uber started off as offering something different to the market but is now so dominant that it just represents it. Over time, difference recedes in importance and something else becomes more important.

What that something else is, however, a source of discussion. Byron Sharp’s books make the case that acquisition is everything, acquisition is largely driven by mental and physical availability (as opposed to differentiation) and that loyalty is more or less just a function of size. This implies that a focus on any sort of differentiation or on improving perceived experience is wasteful when you could focus on improving salience and distribution.

Our Brand Beta analysis highlights that familiarity and therefore mental availability are important for demand but that customers also do differentiate among the brands that they know of and have an ability to purchase.

It is therefore important, at least to a certain extent, to build positive perceptions of your brand and its offer so as not to dissuade those who would otherwise be acquired as a result of your brand’s salience. This creates preference both among new potential buyers and also maintains it among current customers, helping to influence loyalty – at least a little bit!

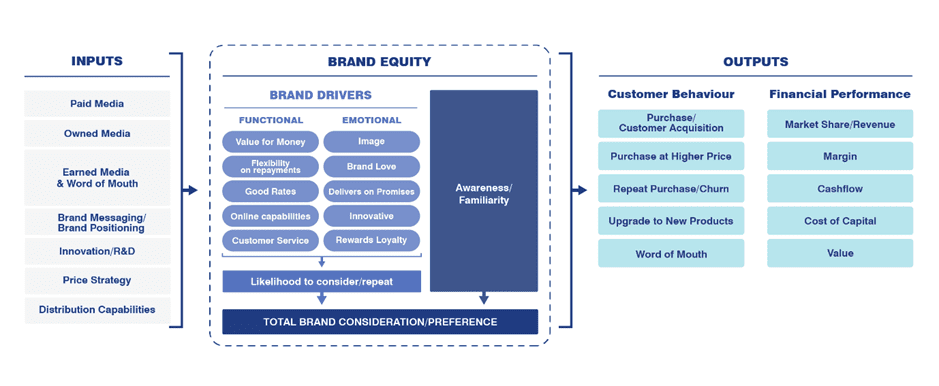

Title: Brand Value Chain. Source: Brand Finance

Our “Brand Value Chain” schematic above helps to show what this means for people who are trying to build brands.

Paid, earned and owned media need to be managed appropriately in order to build Awareness, Familiarity and Salience. These media exposures need to be sustained at a high level for a long period of time. Within short time periods (i.e. months) there is declining effectiveness as multiple exposures to the same audience have diminishing effects.

However, over long periods, all things being equal (e.g. the effectiveness of the advertising) more is better since the more you spend, the more economies of scale you receive in the form both of discounts from media but also in terms of the memorability of advertising.

Additionally, the likelihood to consider needs to be built among those with whom salience already exists. This should be built through a segmentation, targeting and positioning approach whereby the brand’s offer (its “personality” as well as its price, distribution and other functional factors) are matched with those customers that are likely to be in the market for a product or service of the type you are able to offer.

Salience and positive perceptions (i.e. emotional and functional differentiation) therefore need to be built together.

Related to this, one interesting point to end on is the impact of failing to promote your brand. There have been various studies on the impact of stopping advertising but a recent one by the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute reviewed 70 consumer goods brands in Australia in order to see the impact on sales of stopping advertising completely. They found that when you stop promoting brands entirely, sales volume starts to reduce immediately and on average reduces by about 15% a year.

| Index Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Average | |

| Mean Sales Index | 100 | 84 | 75 | 64 | 46 | 42 | 37 | 32 | 28 | - |

| Standard Deviation | - | 33 | 50 | 42 | 30 | 24 | 25 | 23 | 18 | - |

| % Mean Sales change | - | -16% | -11% | -15% | -28% | -9% | -12% | -14% | -13% | -15% |

Source: Adapted from University of South Wales Ehrenberg-Bass Institute,

https://www.marketingscience.info/when-brands-stop-advertising/

This highlights the long-term value of brands. Promotional activities are needed to replenish the stock of salience. Good brand governance, a clear customer proposition, consistent, memorable messaging and a strong product, price and ability to distribute make those promotional activities effective and build differentiation.

However, these activities have effects beyond the current year. They are an investment in the future performance and growth of the business. Therefore the acts of identifying the sources of that value, its potential to depreciate and then the level of investment needed to improve value are a necessary part of understanding, managing and building long-term effectiveness.

So, in short, building brands is a marathon, not a sprint. It needs long-term investment in promotion which is consistent, memorable and includes familiar cues (“assets”) but it also needs a clear customer proposition which is effectively delivered. What this proposition should be and how much you in particular should spend to promote it, however, is the next question. Please get in touch so we can help you figure that out!

References:

- Romaniuk J, 2018, Building Distinctive Brand Assets, Oxford University Press

For more information about how we evaluate brands, visit Brand Valuation Methodology | Brandirectory