Businesses should evaluate the effect of the brand transition, based on demand as well as cost efficiencies. In some cases, poor planning has led to over 20% loss of customers. The stakes are high.

Multi-divisional businesses regularly consider the structure of their brand portfolios. More often than not there is an opportunity to clean up a brand portfolio, exorcise dud brands, and promote new synergies within business divisions.

It goes without saying, any fundamental changes to a brand's identity is a lot of work. Sometimes the sheer enormity of the task is enough for brand transitions to be avoided entirely. On the other hand, sometimes the factors seem right for at least considering the potential improvement in business performance from a change in the brand or a division, the business of acting.

Historically, businesses have looked at brand strategies as a means to rationalise portfolios to create clarity and consistency of brand management. However, this approach implicitly reviews only the cost and complexity of brands, rather than their ability to create value - both improving earnings and reducing cost - overall.

Thankfully more businesses recognise the need to identify all benefits and disadvantages, not just those related to costs. Branding is more than an administrative cost, and we believe much more should be done to make this point of view established practice.

Make strategic branding decisions using hard data. See our consulting services to find out more about what we do to help brands succeed. Or contact us directly. We love to talk.

Context for Brand Transition

There are many triggers that might provide the opportunity to add value to a business through a change of brand. For example:

- M&A: acquiring companies often want to combine marketing efforts with their acquisition to avoid waste and inefficiency. This is frequently a primary concern but often overlooks the impacts on demand from changes causing significant reductions in value.

- Global or regional marketing: it can be more likely your subsidiaries capture the benefit of global marketing if they are under the same brand as that being marketed. Vodafone's global rise was created partly through global sponsorship, which created an impetus to switch its local brands.

- Increased competition: a new brand in the market may indicate a need to hit back with a competitive response. When Uber enters a new market, for example, the focus is needed and competitive sub-brands may need to merge to benefit from joined-up marketing.

- Changing tastes: customers may decide, for example, something traditional is now better than contemporary or transparency becomes more important than simplicity.

- New product launches: shifting the product or service focus of the entity might mean marketing works better under a new positioning. A gas provider launching into the internet of things – for example – may need a change from a positioning focussed on warmth, care and reliability to technology and security.

- An executive order from above: sometimes the board just wants to transition to a Masterbrand strategy with no explanation. Finding the way to minimise risk and maximise the gain from a change is just as, if not more, important than where a specific benefit is identified.

Establishing Whether Brand Transition is Possible

The first step in any assessment is to determine whether a brand transition is even possible to brands.

Often, group companies cannot be rebranded due to a lack of ownership and control, usually meaning 50% or 75%+ of voting rights. Without this, it may be impossible or unwise to rebrand due to a lack of control over its potential use. A lack of support either in the parent or subsidiary company may render the initiative not worth the bother. Regulatory requirements in some industries – in particular, banking – also complicate matters, necessitating ownership hurdles that must be satisfied in order to use or reference a parent brand name.

That being said, where management control exists many companies can and do decide to use different or new brands. These often take the form of a licencing structure akin to Virgin’s business model, where Virgin has no or limited ownership of the underlying companies but manages and protects its brand while extracting a royalty.

Licencing can create issues though, particularly where the brand being licenced-in is owned by a major shareholder. Non-controlling interests rightly scrutinise any action by a major shareholder that does not look arm’s length, meaning that appropriate royalty rates to be used need to be scrutinised and justified carefully.

Internal considerations unrelated to the brand can also become sticking points. Where there are plans to sell the business it would usually not make sense to transition the company’s visual identity. Unless you are planning to licence the brand to the acquiring company rebranding costs needed by the acquirer would likely reduce their bid.

Identifying Branded Businesses With Potential for Value Growth

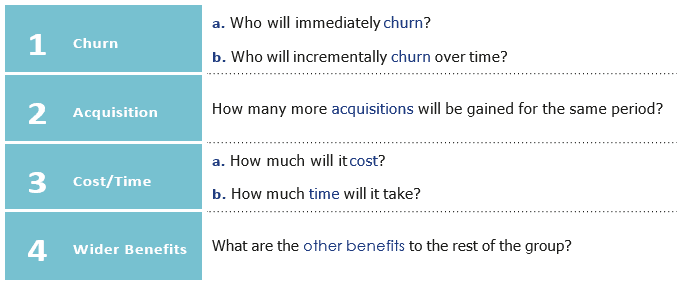

The fundamental questions for establishing an opportunity are:

- How much, if at all, will a rebrand upset current customers?

- How much, if at all, will it entice new customers?

- How much will it cost?

- What, if any, are the benefits to the wider group?

In most cases, there will be implicit, or even explicit, aversion to the new brand. This is driven either through loyalty to the old, or perceptual problems with the new.

A food delivery app in the US, for example, was considering how to reorient the company to fight off a recent entrant that was well-financed and growing quickly. It had recently acquired a competitor in order to eliminate its competition from the market, acquire its customers and combine product development and investment budgets around one, single-branded platform.

After analysing the impact of marketing spend on awareness for the parent and sub-brand, it became clear that the parent brand’s marketing spend was much more effective at driving awareness and user growth than the sub-brand. This finding was attributed to it being a bigger and better brand in almost all market segments. It seemed clear that the plan to rebrand should occur as soon as possible.

However, we reviewed the responses of existing brand customers to the new brand and its product, many of which were negative. 4-5% of customers said they would definitely not, and over 20% probably not, order from the app if it underwent a brand transition the new brand, a number which increased when considering only regular users of the existing brand – the high-value group. This analysis on the rate of potential customer loss was confirmed after reviewing two previously rebranded acquisitions which had seen 15-20% customer losses.

It was also noted that the acquired app was known by a number of potential customers unaware of the parent brand. A switch in the brand would remove a distribution channel for acquiring new customers since those who were aware of the sub-brand, but not the parent, would not know to search for the latter. The risks showed the solution was to rebrand slowly, with plenty of reminders and signposts about the impending switch.

How much, if at all, will rebranding entice new customers?

Fundamentally and across all sectors, customers tend to purchase more from brands when:

- They are aware of the brand;

- They think the brand represents something they like; and

- They are selling a product they want at a price they’re happy with

Assuming the product offer would be the same under either the existing brand or the new brand, the questions to be answered can be narrowed to awareness and the brand’s equity. By brand equity we are referring to the perceptions of the brand held by customers and other stakeholders. Brand tracking and business performance data are therefore the most useful information to be used to review architecture opportunities.

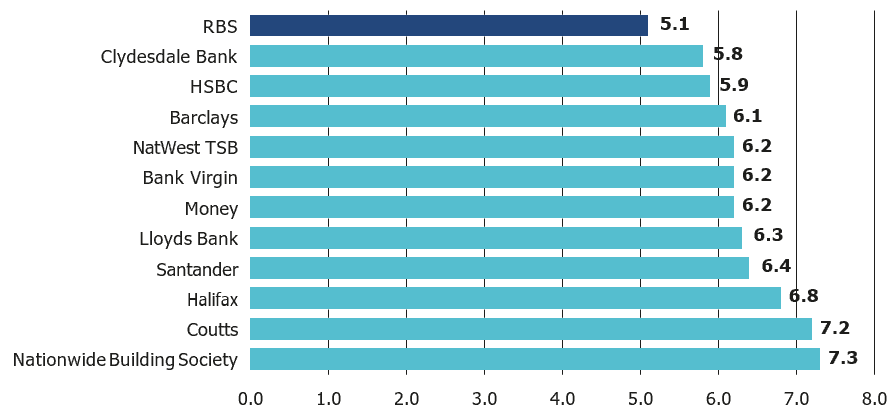

Businesses that are underperforming may represent one such architecture opportunity. Over the last ten years, the RBS brand of Royal Bank of Scotland Group in the UK has been falling in value. RBS’ retail customers were leaving at a faster rate than competitors and new customers were joining more slowly. It was also returning to profitability more slowly than other banks.

Having asked the question “How reputable do you think this brand is?” to a sample of 1000 since 2015, it became clear to us that this underperformance correlated with the brand’s position as the worst perceived big bank in the UK.

In the last few years, RBS has transitioned to NatWest in England & Wales: the group clearly also noticed an opportunity for a reputational revamp 1.

How reputable do you think your brand is?

It is key here to identify the attributes of the brand which customers value most, and analyse those attribute's impact on demand. This is known as drivers analysis, and this will be the best tool for identifying whether there are opportunities from a rebrand.

When Vodafone was embarking on its global expansion strategy, it became clear that in many markets Vodafone was considered superior to the brands of their local acquisitions – on network coverage, international prestige, reliability and many other important drivers of demand – despite not yet being present in the market. Those markets offered the easiest opportunity for value growth since little more than switching the brand identity was needed to create a benefit.

How much will it cost?

Rebranding requires investment in management time, research, training, brand guidelines, on-going performance and compliance audits to name just a few of the main areas. It necessitates the updating of everything from packaging, uniforms, delivery vehicles and delivery systems to business cards, advertising campaigns and stationery. It also creates the need for incremental investment explaining the change through advertising and promotion.

These costs can be significant. A shipping company with fifty thousand containers each costing $1,000 to rebrand will face a cost of $50m to complete what would only be a small part of the overall transition, for example.

Just as the drivers of demand for brands differ between sectors, so do the activities and costs associated with branding and marketing and therefore what needs to be done for a rebrand to be successful.

One of the first steps in a rebrand is, therefore, to identify what will need to be updated and how feasible, and costly, any changes are. A step usually best completed after speaking with brand identity management specialists and internal teams closer to the action than central office.

What, if any, are the benefits to the wider group?

The benefits to the group depend on what brand transition and architecture strategy is being pursued. Building a single-brand group structure can have benefits including:

- Build Confidence and Trust: The perception of greater scale can create greater trust and willingness to deal with the brand amongst customers. For example, a business needs to prove that it can offer global service to a high quality may want to move to one brand to increase the likelihood of winning work with multinationals.

- Create a Brand Culture and Share Best Practice: A single brand across a portfolio can help employees to feel part of the brand group, and to operate consistently across national and cultural boundaries.

- Generate Marketing Efficiency: It can enable above the line expenditure to be used more efficiently, benefitting all companies within the group, and creating other efficiencies in production costs. In particular, global sponsorship and celebrity endorsement campaigns will likely have the same effect as local advertising for less cost when enough countries are under one brand.

- Maximise Growth Potential: A stronger, larger brand can help to enable market entry and secure new business partnerships. Combining brands can also increase the sale of similar or bundled goods and upgrades to existing purchases.

Brands are not always switched to become the same as their parent because transitioning to a multi-brand structure can help to build value by:

- Allowing Targeted Propositions: Strong brands can be tailored to different businesses and customer segments. Highly targeted use of marketing spend - focusing on specific audiences can be more efficient and effective.

- Capitalising on existing Brand Equity: Using a locally known brand rather than a global master brand could benefit from existing perceptions rather than having to build them from scratch.

- Reducing the Risk of Contagion: Running multiple brands prevents the risk of reputational damage in one part of the business spreading to the whole organisation.

- Creating Strategic Flexibility: Separate brands allow maximum flexibility for strategic activity (e.g. M&A, divestment).

The effects of each benefit can be modelled either by analysing the impact on-demand or on cost. This is important since transitioning to a new brand can frequently be value-destroying. Balancing any potential loss with a wider benefit is therefore key in establishing whether the move is worthwhile.

Main Takeaways

Due diligence is key. An informed and data-based understanding of the health and strength of your brand is crucial if you are going to make any changes - especially one as big as a brand transition.

Before starting a transition programme, it's essential to do this due diligence in order to:

- Get a sense of brand's role in your company's overall strategic direction

- Understand internal stakeholders' concerns, any obstacles that will cause and how to get them on side - if necessary.

- The steps for further analysis and planning and the teams, agencies or data that you will need to help you.

The payoff you receive from embracing due diligence and establishing a sophisticated brand measurement system is not just the short-term limitation of risk, but in the long-term benefit of confidence and control in your brand strategy.

Brand Transition 101

To Rebrand or Not To Rebrand: When Should You Rebrand an Acquisition?