Following the economic downturn brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, brands may be asking themselves how they can overcome unprecedented crises. How can marketers navigate the shaky landscape to protect brand value?

There has not been a serious recession in the UK since the great crash of 2008-2009 (Subprime debt crisis) although there have been two serious economic downturns in 2011-2012 (European debt crisis) and again in 2015-2016 (Global Oil price war). Commentators have suggested that the world is long overdue for a major recession, which conventional wisdom says comes about once every 10 years.

The definition of a recession is two-quarters of negative GDP growth. Several European economies, including the UK, have flirted with recessions in recent years (no doubt connected to Brexit fears), but the actual effect has been relatively minor, and, apart from (and perhaps because of) a slump in Sterling in 2016, the UK economy has remained strong and growing for the last 3 years.

Has the pandemic asked hard questions of your brand? See our consulting services to find out more about what we do to help brands overcome crises.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered the long-anticipated downturn, developing far faster than anyone could have imagined. There seems to have been a complacent belief that it was largely a Chinese or Asian problem and that Europe would cope better and with less severe consequences.

However, since December 2019, when the first outbreak occurred in Wuhan, the Chinese government has taken unprecedented action to control the disease which has now plateaued there. The huge Chinese economy is apparently getting back into action and even offering help to others. Meanwhile, European countries have taken little action, resulting in the outbreak growing exponentially and forcing most European economies to now enter a state of lockdown.

One consequence of the pandemic has been a reduction in global demand for oil and gas which has caused a disagreement between members of OPEC about voluntary curbs on oil supplies to keep prices high. Unfortunately, Russia and Saudi Arabia cannot agree on supply curbs and quotas, resulting in Saudi Arabia opening the flood gates and driving oil prices down from $70 a barrel to below $0.

This has crucified shale oil producers in the US and all the oil majors, who require high oil prices to keep their more expensive wells profitable. This has made matters worse in an existing health crisis, with several oil-producing economies and companies being badly hit. It is quite unusual for there to be an immediate recession, stock market slump, supply and demand-side contractions, an oil price collapse, and massive unemployment simultaneously. In fact, it’s unprecedented, causing some to predict this to be the worst downturn in 100 years.

Against this background, it is being seriously suggested that the UK will be locked down for a minimum of 3 to 6 months, with GDP predicted to shrink by 10% in the first half alone. The government has scrambled to provide monetary and fiscal stimulus and support, with bank base rates being virtually zero for some time and many taxes being cut or deferred.

Direct loans and grants will surely follow to prevent the economy from melting down, particularly in specific sectors like aviation, transport, hotels, leisure, and retail. However, there will be significant unemployment and some industries will be seriously damaged despite government assistance.

Interestingly, the crisis has revived nationalistic economic policies, with most major economies providing very substantial financial help to prevent ‘strategic’ national industries going to the wall, even though such action is explicitly banned under the EU and WTO competition rules.

Vulnerability to long supply chains is also making countries consider rebuilding national industries that have long been closed by Asian manufacturing competition. The pharmaceutical and medical equipment sectors merely a few examples of where reliance on China could slow the process of dealing with the health crisis.

What is the impact on brand value?

The immediate impact of the crisis is still difficult to entirely predict, depending on how severe the pandemic gets and for how long. It also depends on economic and social policy responses by governments.

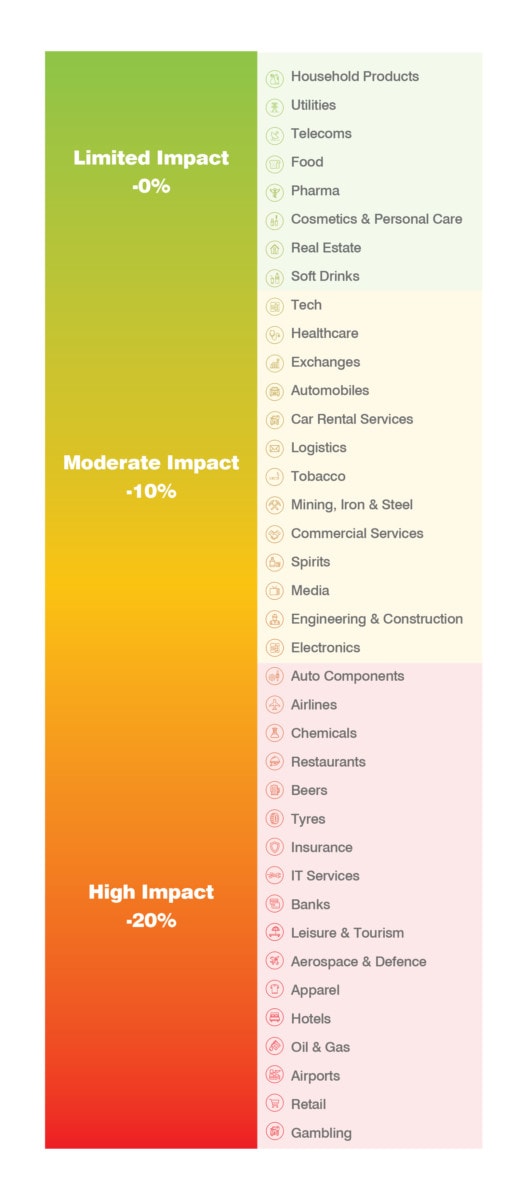

Although the final impact is hard to predict, we have summarised the stock market’s view by assessing the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak based on the effect of the outbreak on enterprise value as of 18 March 2020, compared to what it was on 1st January 2020. We conducted this analysis and separated the effect by sector, then classifying each sector into 3 categories based on the severity of enterprise value loss observed for the sector in the period between 1st January 2020 and 18th March 2020.

The overall loss of enterprise value has been upwards of $8 trillion, constituting more than 30% losses in some sectors. The hardest-hit sectors are airlines, leisure and tourism, aviation, and aerospace and defence. The global airline industry has called for up to €200 billion in emergency support and Boeing called for €60 billion in assistance for aerospace manufacturers.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has said most carriers will run out of money within two months as a result of borders being closed to arrivals as governments order a lockdown to contain the coronavirus outbreak. A large number of major airlines have grounded most of their fleets and announced plans to lay off thousands of staff as they now confront a crisis unlike anything ever seen before in the airline industry.

The luxury industry - also classified as high impact - is feeling immediate effects from the COVID-19 outbreak. The highest spend on luxury comes from China, where the outbreak began, and as the health epidemic takes its toll on the high street and forces shops to shut, the impetus for luxury purchases will be the first to fall.

A crisis is no time to recede. Here are 5 Reasons to Increase your Marketing Spend During an Economic Downturn.

Which brands will survive the carnage?

Some economists argue that the shakeout of weak companies and brands is a desirable process.

Persistently low interest rates since the 2009 financial crisis have kept ‘zombie’ businesses and brands on life support when they should have gone bust. Heavily indebted, inefficient, and slow-growth companies should, they argue, be allowed to die to free resources for new market entrants. Brands like Carphone Warehouse, Laura Ashley, and Debenhams spring to mind.

The national unemployment rate was, until recently, only 3% of the UK working population, which is deemed by many economists to be full employment. It certainly is in London, which explains the huge demand for immigrant labour in the booming South East region. Full employment constrains the labour supply for fast-growing new industries and businesses.

Seldom has the world been such an unpredictable and risky place for marketers and their brands. The $64,000 dollar question is which brands will actually survive the carnage. We have been tracking brand values continuously since 2007 when we first started publishing the Brand Finance Global 500 ranking of the world’s most valuable brands. We have tracked how brand values have fluctuated during the three major economic downturns experienced in 2009, 2012, and 2016.

There are 405 brands whose brand value can be tracked continuously since 2008, through all recent recessions. We found that during the three recessionary periods, average brand value growth was lowest across the whole sample. We also found that some brands habitually fall in value during downturns and that they come from specific sectors.

Interestingly, banking is particularly vulnerable, with 74 of the Consistent 100 Fallers being bank brands. This is perhaps not really surprising because banks are the backbone of the wider economy and are highly leveraged. If their borrowers default it can rapidly undermine the integrity of the banking business and the balance sheet. In addition, recessions usually lead to lower interest rates and therefore constrained margins for banks. In many respects people don’t appreciate that banking is a highly leveraged, high risk, low margin business. So weaker banking brands fare worse. High quality, higher-margin banking brands like American Express and Coutts perform better during recessions.

Looking at the Consistent 100 Winners, banks are also well represented with 30 of the top 100 brands listed. However, telecoms and a wide variety of other sectors are featured. 14 of the top 100 Winners are telecoms companies, perhaps because the demand for communications and entertainment grows during recessions.

The notable feature of our long-term analysis is that strong brands perform better, whichever sector they are from. Considering brand strength, we find that from 2008 to 2019, the Consistent 100 fallers have average Brand Strength Index (BSI) scores of 66 while the Consistent 100 winners have average BSI scores of 70 out of 100. This finding is in line with other research we have conducted which correlates brand strength with overall stock market out-performance. AAA+ brands, as measured by our brand evaluation process, consistently outperform the S&P 500.

The COVID-19 pandemic is now a major global health threat and its impact on global markets is very real. Worldwide, brands across every sector need to brace themselves for the Coronavirus to massively affect their business activities, supply chain and revenues in a way that eclipses the 2003 SARS outbreak. The effects will be felt well into 2021.

One thing we have to consider is that all business valuation and brand valuations are conducted on a Fair Market Value basis which considers what a willing buyer will pay a willing seller, in an arms-length transaction, for the subject asset. Willing buyers demonstrate that they are willing to pay a premium for strongly branded companies.

What this says is that they believe that strongly branded companies are expected to have more reliable demand, lower cost profiles, more efficient marketing leverage, and lower cost of capital for longer into the future, for which they are prepared to pay an investment premium.

So much for macroeconomic effects created by the current health crisis and so much for the average performance of brands over a long period, through thick and thin. The question now is how specific brands are likely to fare during the current downturn. It is early days, but trends are already emerging.

All brands in the airlines, hotels, retail, hospitality, leisure, luxury, and beer sectors are suffering. Brands like British Airways, Virgin Atlantic, and Lufthansa have almost unbelievably all suggested they may go bust. Many will go bust if they are not bailed out to survive.

Which brands are thriving in the wake of COVID-19?

Other sectors are doing well. Brands involved in all aspects of medical and health provision (BUPA, Nuffield, Boots, GSK) are all in the front line and are booming.

Brands involved in online retailing (Amazon, Walmart, and Ocado) are all performing strongly. In fact, Amazon has announced that it will be recruiting 100,000 extra staff to cope with increased demand as customers self-isolate and get their provisions and products via the internet.

Brands involved in communications and entertainment (BBC, Amazon Prime, Netflix, Vodafone, Orange, Verizon) are all experiencing significant uplift in demand as bored people sit at home both working and trying to entertain themselves.

Many brands in the business to business world seem to do well whether things are bad or good. Deloitte, which has mobilised in an unprecedented way to help its staff, clients, and governments worldwide, will be doing well. We also saw PwC, EY, and KPMG perform well in previous recessions. They move fast to fulfil the needs of companies in recessionary and non-recessionary periods alike.

However, it is not all doom and gloom. Some brands will fare better under COVID-19, with Amazon, Netflix, WhatsApp, Skype, BBC, and BUPA all booming.

Certain consumable and household product brands are also booming. Paracetamol analgesics, Andrex toilet paper, Marigold gloves, and various alcohol brands are all in big demand.

Some brands are not looking to enhance their financial performance but to build reputation and goodwill rather than revenues, at least in the short run. For example, The National Trust has waived all entrance charges for people on lockdown who want a walk in the great outdoors. This will build their brand in the long term. No doubt there are many other altruistic brands that will be remembered for such gestures.

How should brand managers react to economic crises?

It is easy to argue that brand managers should lay low and wait for the worst effects of the crisis and recession to disappear. However, as The National Trust action demonstrates, such moments do create opportunities to present their brands well to the world and to their stakeholders, particularly to internal stakeholders. Every brand manager should consider what is authentic, appropriate, and casts their brand in a favourable light for the time when things improve.

Our own data supports this phenomenon. Amazon has been the world’s most valuable brand for the last two years, having grown at breakneck speed for the last 20 years. During the financial crisis in 2007-2010, Amazon increased its level of marketing spend relative to revenue consistently every year and by 2010 the level was 30% higher than in 2007. In 2010, its brand was 143% more valuable than it was in 2007. eBay, by comparison, reduced its level of sales and marketing investment by 13% and saw its brand value fall by 22%. Amazon’s fortitude during the crisis years buffeted it from many of the issues facing retailing and set it up for its astronomical growth in later years.

On which note the other $64,000 question is should advertising budgets and activity be curtailed? The simple answer is no. In fact, from a contrarian perspective advertising and promotion should be increased. Firstly, the cost of media usually decreases in recessions. Secondly, consumers are more receptive and have more time to absorb brand messages. Thirdly, if the messaging is appropriate it can have a more powerful emotional effect. This is why PIMS and LBS found that during the 1993 recession those companies which advertised consistently and heavily during the downturn experienced significant growth in market share in the two years following the recession.

The moral of the story is get the message right, get out there, and communicate. People are responsive and looking for reassurance from brands they like, trust, and respect at a crucial and scary time in their lives.

Managing Your Brand in a Crisis 101

How Has COVID-19 Impacted Brand Value and What Can You Do About It?

5 Ways to Manage Your Brand In Times Of Crisis

Managing Your Brand in Times of Crisis: Lessons From the Past

How Brands Can Overcome Unprecedented Crises